Over the course of his academic career, David Lahti has lived in many worlds. For his PhD in philosophy, Lahti wrote a dissertation on the ways that science can and cannot contribute to our understanding of morality. Later, he completed a PhD in ecology and evolutionary biology, where he studied birds. Today, his lab at Queens College, City University of New York, studies topics ranging from culture in birds (especially their song) to human cultural evolution.

Cultural evolution, a field that seeks to incorporate numerous research strategies to better understand the flow of ideas and human cultures through time, lies at the confluence of his different disciplines.

The interdisciplinary field only organized into a formal society in 2016, bringing together neurologists, behavioral ecologists, psychologists, evolutionary biologists, archaeologists and anthropologists. By incorporating all these different perspectives, researchers hope to better understand big questions about humanity, like why some religions catch on more than others, how racism is perpetuated, and where we learn morals and values.

But combining so many disciplines comes with a number of challenges. “It’s a nascent field and that’s why we haven’t ironed out wrinkles and formed common questions,” Lahti says. “Another reason is we’re all coming with baggage from our parent fields.”

Among these unresolved common questions is the definition of cultural evolution itself. As Alberto Micheletti, Eva Brand and Ruth Mace write in “What is cultural evolution anyway?” the term can be used to refer to a phenomenon (culture changing over time) or the approaches used to study this phenomenon. These authors argue that “cultural evolution” should be reserved for the phenomenon itself, allowing researchers to use different theories and practices to study it.

The intertwined nature of cultural practices and genetic evolution is evident, for instance, in the ability of some humans to digest milk long beyond infancy.

Researchers now know that people in different African cultures were consuming dairy products as much as 6,000 years ago, before they developed genetic mutations that enabled the production of the enzyme lactase into adulthood. A culture of eating dairy led to the spread of a significant genetic mutation.

This is an example of cultural evolution happening on a population level, but cultural evolution can just as easily have impacts on individuals (like a child choosing to support a different political party than their parents) and the built environment (constructing certain forms of shelter based on materials available and climate conditions).

For researchers who want to start tackling other questions in cultural evolution, Lahti agrees that defining fundamentals is an important step. Even some of the most common words might not be understood the same by everyone who uses them. He points to two terms that quantify the movement of ideas: transmission bias, which is anything that might hinder or help an idea get from one person to another; and transformation bias, which are the ways that an individual might change a certain idea, either by simplifying it or changing it in their own head before sharing it.

For Lahti, the standard definitions leave out important aspects of human culture. “Individual innovation, environmental effects, individual trial and error learning, things that come into our head from other people,” Lahti says. “It’s not like anyone said they don’t exist, it’s just that when you’ve defined things a certain way, you’ve ignored other considerations.”

But combining different approaches is also what makes the study of cultural evolution such a unique discipline. One of Lahti’s former PhD students, Mason Youngblood, studied a pattern of birdsong that changed over the last 50 years, as well as the role of music sampling in hip hop since 1970. Being able to follow the flow of both birdsong and hip hop artists is possible due to the increase in computational power that researchers now have at their disposal, but also comes from bringing together questions that are normally asked by different disciplines. The collaborative nature of cultural evolution is part of what helps researchers reach new insights, even if it can also lead to misunderstandings.

-

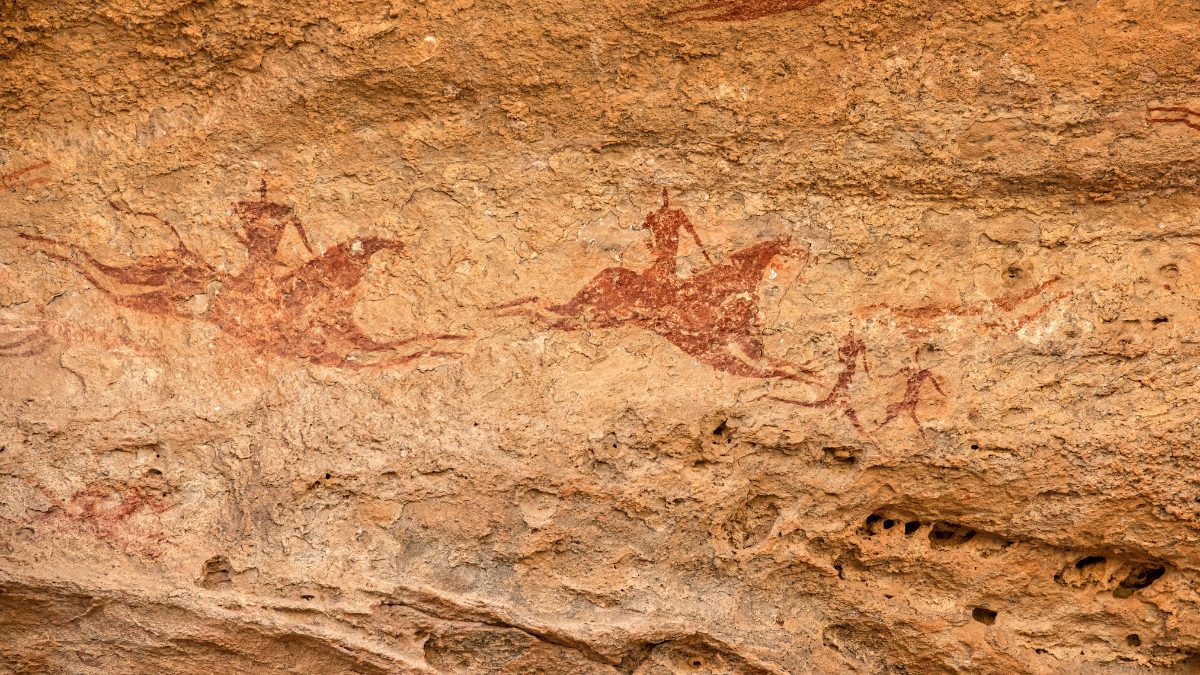

Illustration by Jin Xia

Paul Wason, who has a background in anthropology and archaeology and works as the senior director for Culture and Global Perspectives at the John Templeton Foundation, agrees that the nebulous nature of cultural evolution is both a strength and a weakness. “One of the lively interesting things about it is you can’t pin down its boundaries. You can’t say ‘this is the canon of accepted wisdom on the subject, and you can’t question that,’ because someone’s going to question it. I think it may coalesce and I’m not sure whether that would be good for it or not. It would probably increase the amount of research and give you more professors working on it, but that also sets boundaries.”

Researchers still have to approach the field with caution and humility. For some, the neighboring discipline of “sociocultural evolution” is directly tied to social Darwinism, a discredited theory of human development used to justify racism and eugenics. In the 19th century, for example, many social scientists believed that societies proceeded through a unilinear pattern of development, from “savagery” to “civilization.”

“Contemporary cultural evolution is at great pains to separate itself from that history,” Lahti says. “Any field that deals with matters that can be misinterpreted in a way that can be harmful to people socially has to be very conscious of its responsibility. It’s not so likely in optical physics or inorganic chemistry, but it is very possible when we’re talking about ‘where do ideas come from’ or ‘why do they perpetuate’.”

Members of white supremacist groups, for example, will create informal journal clubs “dedicated to dissecting population genetics papers and sorting them into those that support a white nationalist ideology and those that don’t,” reported Michael Price for Science.

“We use an abundance of caution because we don’t know what the public is going to think when we talk about things which are not at all consistent with racism or xenophobia or eugenics, but we’re using terms [that can be misunderstood and appropriated],” Lahti says.

Still, he has found himself becoming more optimistic about how the researchers studying cultural evolution have started exploring big questions about human life.

“I would say cultural evolution is poised to unify historical sciences with respect to what we’re like as human beings in a way that no single field has ever been able to do before,” Lahti says. “Why do we have the kinds of families we do, how come things are changing in any given culture—those difficult questions that cause most of us to throw up our hands—I think we may be able to say something about them.”

Lorraine Boissoneault is a Chicago-based writer covering science and history. She is the author of the narrative nonfiction book “The Last Voyageurs.”