Ask most people to name someone who epitomizes intelligence, and you’ll get Einstein. We’ve come to equate intelligence with the scientific kind he embodied—analytic, rational, precise, explanatory. And perhaps rightly so. Scientific intelligence has undoubtedly been revolutionary; it has given us antibiotics, space flight, the internet. It is among humanity’s greatest achievements, and we’re right to admire it. Yet, as the German sociologist Max Weber pointed out more than a century ago, it comes with a cost.

Weber saw modern science as a driver of disenchantment, stripping away the sense of mystery, magic, and the sacred from reality. This mode of disenchantment is not restricted to the research lab, but characterizes the applications of science as well, from Frederick Winslow Taylor’s “scientific management” to the Silicon Valley mantra “move fast and break things,” and the breakneck pace of development of Artificial Intelligence systems.

What makes scientific intelligence alienating, I would argue, is not the science itself but an underlying logic consisting of three main elements:

(1) Domination: the imperative to control and master; we see this in Descartes’ notion of becoming “masters and possessors of nature”;

(2) Extraction: the impulse to reduce everything to means-ends calculation. Heidegger critiqued modern science and technology as “enframing” the world, rendering reality into “standing reserves” or resources for exploitation.

(3) Fragmentation: the reflex to break wholes into hyper-specialized parts. Weber warned that rationalization and specialization were producing “specialists without spirit,” and Thomas Kuhn showed how scientific paradigms channel inquiry into narrower puzzles, often obscuring the bigger picture.

I call these three elements the DEF Logic.

These defaults are powerful, and they certainly influence the way science is practiced and applied. But they are not the whole story.

The Enchantment of Science

Over the past five years, my team and I have surveyed more than 3,000 scientists and interviewed more than 300 of them at length (see here and here). Our research found something Weber never anticipated. For most scientists, inquiry does not disenchant the world; rather, it deepens their sense of enchantment. Beneath the DEF logic lies another current that animates science; it is quieter but no less real. While scientific intelligence helps us understand how things work, there is a different mode of intelligence that orients us to why things matter.

Psychologists describe “spiritual intelligence” as the capacity to recognize meaning and intrinsic value, to integrate that recognition into a coherent understanding of self and world, and to translate it into wise and constructive action.

In the lives of scientists, we’ve found that three facets of this kind of intelligence stand out—Reverence, Receptivity, and Reconnection—which run counter to the DEF logic.

Reverence

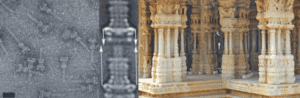

More than four in five scientists we surveyed tell us they regularly experience, in their work, a profound sense of respect for what they learn. This is exemplified by an Indian microbiologist I spoke to. Showing me cryo-electron microscopy images of the microbial needle complex of Salmonella, she told me:

“If I don’t tell you that this is a bacterial needle, you may easily mistake this for one of those beautiful stambhas in archaeological sites…They make this kind of delivery-system needle, which if we even think of manufacturing, we may take ages to do so—and they do it within minutes…If I were a painter, I could have drawn it. It is this beautiful!”

A cluster of bacterial injection system needles (left) and a single bacterial needle (center), credit Dipshikha Chakravortty. “Stambhas” or temple pillars in Hampi, India (right), credit Roman Saienko (Pexels).

For this biologist, this experience of reverence has fostered a posture of care. Instead of wanting to dominate and conquer bacteria, she yearns for us to figure out a way to live harmoniously with them, even if such solutions may seem presently out of reach.

Receptivity

Again, more than 80 percent of scientists in our study report that reality regularly presents them with new mysteries. Such moments run contrary to the tendency to treat phenomena as nothing more than data to be harvested or as material to exploit for a quick publication. One UK physicist described how his encounters with reality regularly confront him with big questions such as “why is there something rather than nothing?” He told us, “If I actually see something like a sunset, then [this question becomes] more powerful in my mind. The sense of mystery will become more powerful.”

Or as an Italian biologist told us:

“When you encounter something you still can’t fully explain scientifically…then a sense of magic remains. A single human cell involves millions of coordinated processes. Billions of these cells harmoniously working together in our bodies: that’s breathtaking.”

Receptivity is not passivity or sentimentality. It is the discipline of letting the world give itself to us—allowing questions to emerge and deepen before we rush to convert them into utility.

It is gratitude for the sheer givenness of things.

Reconnection

Science undoubtedly depends on analysis and specialization. But analysis without a sense of the bigger picture breeds alienation, turning us into Weber’s “specialists without spirit.” Many scientists described counter-moments when their work pulled them back into a felt sense of belonging. A British biologist recalled sitting on a boat in a sea alight with bioluminescence and feeling deeply connected to everything:

“That sense of understanding that all of those little glowing lights are individual organisms that are glowing for their own reasons…that was a profound experience…It felt spiritual, just in that sense of being connected and being part of that whole tapestry of being, and being a small [and] insignificant part of that tapestry.”

Reconnection knits back what fragmentation tears apart. It helps us recognize that we are part of nature, we belong to it, we are deeply connected to it. And science is a privileged pathway to such experiences.

Spirit and System

The point is not that scientists are uniquely spiritual, but that their experiences show how even within the heart of modern rationality, another kind of intelligence is alive. What we see among scientists is instructive for all of us, because the deeper principles they cultivate—reverence, receptivity, reconnection—are valuable far beyond the lab bench.

Of course, we should also exercise caution against a naively positive view of spirituality. Recent research in the sociology of religion reveals that (1) context matters: what counts as “spiritual” varies across cultural and historical contexts, and what’s presently in vogue is not universally shared; (2) community matters: spirituality is sustained by shared practices, exemplars, and discourses that cannot be cultivated in isolation; and (3) power matters: spirituality is not immune to power relations, but can be co-opted and manipulated into a tool of control rather than transformation.

But even in the best circumstances, while individual scientists may find reverence, receptivity, and reconnection personally meaningful, their institutions rarely value them. The DEF Logic still governs the publish-or-perish treadmill, corrodes lab culture, and licenses the misuse of science. Our broader economy runs on the same logic, which also propels the acceleration of AI systems. One of the leading AI companies defines intelligence as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.” Intelligence collapses into productivity; questions of meaning and value are rendered externalities.

The danger here is that spirituality gets confined to private wellness hacks while “real” decisions obey DEF imperatives. Worse, spiritual intelligence itself could be co-opted—turned into another metric like IQ or EQ, harnessed to evaluate and control.

Rather than serving the status quo, could spiritual intelligence help us reimagine the design criteria for new technologies? What might AI systems look like that were intentionally designed for reverence instead of domination, receptivity instead of extraction, reconnection instead of alienation?

The scientists I’ve studied make clear that the choice we must make is not between science vs. spirituality. Instead, the choice is between which posture toward reality we adopt:

one that exploits the world as raw material, and another that receives it as a gift.

The same choice confronts us in the systems we build. We can amplify the DEF logic until we can no longer hear the planet or each other. Or we can re-tune our institutions and technologies to the quieter signal already alive in the best scientific work: reverence, receptivity, reconnection. Our future depends on which signal we choose to amplify.

Brandon Vaidyanathan is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Institutional Flourishing Lab at The Catholic University of America. His research examines the cultural dimensions of religious, commercial, and scientific institutions. His books include Mercenaries and Missionaries, Secularity and Science, and Rebuilding Trust. He is also the founder and host of the Beauty at Work podcast and YouTube channel.