The evening began like a thought experiment.

A Caltech physicist stood before a room of select writers, filmmakers, and other Hollywood creatives, reflecting that some of his most meaningful scientific insights and inspirations have come not from equations but from stories. Growing up, he said, shows like Star Trek sparked the very questions physicists still try to answer—proof that imagination in the arts can precede scientific theory.

“Writers show us what could be,” said Rana Adhikari, Professor of Experimental Physics at Caltech, “and then we go see if it’s real.”

The room filled with laughter, but something electric moved through the air, that moment when imagination and evidence seemed to orbit the same truth.

What if art is as essential to science as data? What if story and science collectively expand our understanding of reality?

Hosted by the Science & Entertainment Exchange, with support from the John Templeton Foundation, the night felt less like a lecture than a reminder: discovery begins with wonder, and story gives that wonder form. Creativity is not just an accessory to science but an unseen law, the hidden physics of how new worlds are born.

The Room Where Wonder Happens

It’s a clear autumn night in Los Angeles. At the home of Oscar-nominated screenwriter Jon Spaihts and filmmaker-actor Johanna Watts, storytellers and scientists gather beneath the stars—by the pool, over a savory dinner, with wine and white-and-gold macarons so luminous they shimmer in their bowl.

Conversations ripple across tables: Christopher Nolan’s Batman, artificial intelligence, quantum mechanics, super-aging, and bioengineering solutions for women’s health. In this crowd, such talk isn’t small—it’s speculative design, the blueprint for tomorrow’s world.

Soon, the group is invited to take their seats, and Rick Loverd of the Science & Entertainment Exchange opens the night:

“Why is it that when I was a kid, the scientists were the good guys in the movies—and now they’re the bad guys?” he asks. “That’s why we’re all here tonight.”

Then David Nassar of the John Templeton Foundation follows:

“We want people to be curious about the wonders of the universe,” he says. “Maybe stories emerge from these conversations—maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow—but stories that help achieve that mission.”

Around the room, heads nod. Physicists, screenwriters, neuroscientists, and documentarians share the same impulse: to make sense of what can’t yet be seen.

How Imagination Shapes Discovery

When Adhikari takes the floor, his humor is quick to disarm the room.

A core experimental physicist in the Nobel Prize-winning LIGO collaboration—and now a key architect of Cosmic Explorer, the next-generation U.S. gravitational-wave observatory—Adhikari has spent two decades chasing signals at the edge of known physics: precision measurements designed to push beyond the limits of what we understand about gravity, quantum mechanics, and the nature of space and time.

But tonight, his data gives way to delight.

“I’ve never talked about this before,” he says, glancing at his laptop. “This is a little bit of a pitch.”

Using the lingo of Hollywood storytellers trying to sell an idea, he draws a laugh. It isn’t the data he hasn’t shared, it’s the story behind it: how imagination and art have shaped the way he thinks about physics.

Adhikari described himself as “basically a mechanic in high school.” “I liked taking things apart, fixing engines,” he says, with deadpan humor. “Then I started reading Einstein’s relativity and thought, ‘I’m not so sure.’”

His hands-on approach, honed from years of tinkering and building, later became his unexpected advantage in the halls of academia—a practical sensibility that opened doors at MIT and Caltech.

The crowd laughs—but they’re listening now. In that offhand remark, the room hears the essence of scientific imagination: the courage to question even what’s considered sacred.

He moves to a slide from the movie Interstellar. “Here’s my buddy Kip Thorne,” the Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist who served as scientific advisor and executive producer on the film. “He brought producers into my lab, and the script changed.”

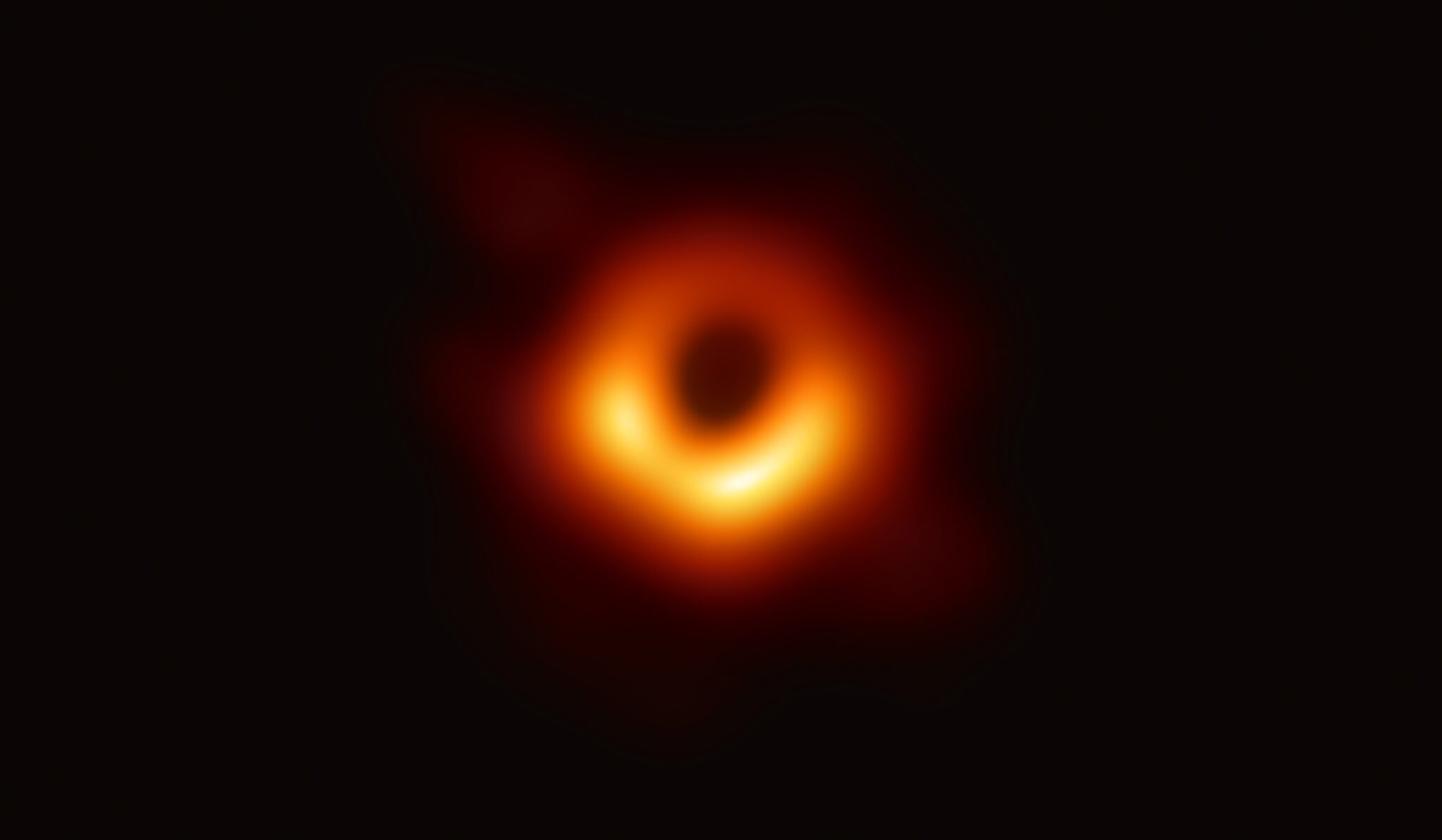

Adhikari explains how the movie’s CGI team invented new mathematical tools to visualize black holes.

“We didn’t actually have the science to show what we wanted,” he says. “So they came up with new ways to simulate black holes—and it turned out to be real science.”

Then he shows a later collaboration between Thorne and artist Lia Halloran. “Her paintings express what’s really going on in black holes better than you can ever do with scientific visualizations,” he says.

He pauses, just long enough for the insight to land. “It’s the act of storytelling—what you choose to emphasize—that makes discovery possible.”

The audience leans in as Adhikari reframes the scientific method as something deeply human: imagination plus precision, myth meeting math.

From Star Trek to the Frontiers of the Cosmos

Then his face lights up.

“I was big into Star Trek: The Next Generation,” he recalls. “I met LeVar Burton on a plane and told him, ‘You’re the man—you don’t understand how many times we’re in the lab and say, remember, it’s like that one episode where he does that thing.’ It’s such a good scientific shorthand.”

He describes an episode in which a black hole threatens the solar system.

“And they say, ‘All you have to do is change the gravitational constant of the universe.’ And I thought, maybe I can do that too.”

He literally took the plotline from Star Trek and turned it into a real paper.

“Today,” he adds, “a seminar speaker at Caltech said, ‘Hey, I’ve read that paper of yours and I’m thinking about doing an experiment on this idea.’ … So great—thanks to Star Trek!”

The room lifts into delighted laughter. What began as fiction now fuels discovery.

The Art of Not Knowing

Adhikari plays the sound of two black holes colliding—“a space-time microphone,” he says, and notes that in some parts of the universe, time doesn’t pass at the same rate.

“If you get three quantum physicists together and we’ve had two glasses of wine, immediately we jump into, ‘What does it all mean?’” says Adhikari.

He pauses, reflective now. “There’s all this Einstein talk, there’s all this quantum talk, entanglement, spooky—all this stuff going on,” he says. “But what does it really mean about what’s actually going on in reality? What I think is that there are deeper rules of reality underneath it all. We just don’t know what they are yet.”

“Some days I feel like all of physics is just a made-up language that helps us agree on what we’re seeing,” he recalls telling a colleague one day. “He told me, ‘I don’t know what the [expletive] is going on, but I want to find out before I die.’”

The Physics of Meaning

“All your high school teachers are wrong,” Adhikari jokes. “That stuff they teach you…that’s only true if space is flat. Space is not flat.”

Then, in a single breath, he turns comedy to revelation: “Quantum physics and also the whole Einsteinian relativity—those are stories we tell ourselves that are consistent with what we see.” This doesn’t mean they’re ultimate truth, just the story that works for now.

When the floor opens for questions, they range from philosophy to faith.

Can physics ever explain why we exist?

Where does spirituality fit into science?

What gives you hope about the future?

Is there a place for God in all this?

“Everybody’s spiritual at some level,” he says. “There’s no Newton’s equation that tells me to be nice to people.”

What gives him hope? He points to the way imagination begets invention—from Star Trek to published research, from CGI to new mathematical models—and to the power of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“We have to have more of this mixing of people with different backgrounds,” Adhikari says. “Otherwise, as a species, we’re just going to grind to a halt.”

Some things that sound like science fiction now—even teleportation—may one day be routine, he suggests: advances that, if described today, “you would say it’s magical.”

Because before every great revelation, someone boldly imagines it first.

Alene Dawson is a Southern California-based writer known for her intelligent and popular features, cover stories, interviews, and award-winning publications. She’s a regular contributor to the LA Times.