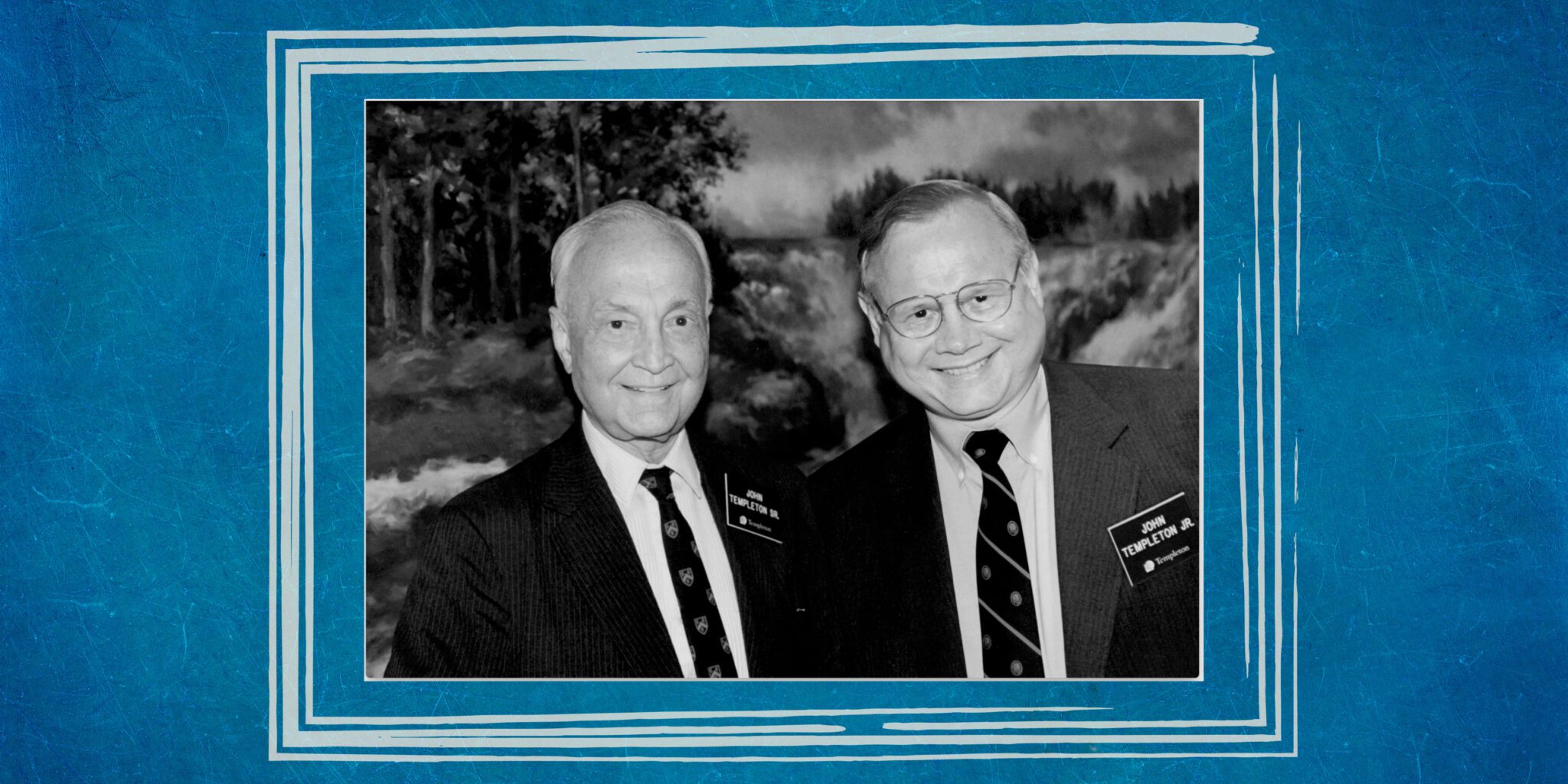

The following remarks were delivered by Heather Templeton Dill, President of the John Templeton Foundation, at an event celebrating the 10-year anniversary of the Jubilee Centre. The speech has been edited for length.

My Dad often told a story about a meeting he had with his father in the days when Dad ran the John Templeton Foundation and reported regularly to his father about the work of the Foundation. On one occasion, Dad was looking forward to sharing details about the work that he had supported. He spoke about the number of people who attended a conference, more than expected. He pointed to articles published and citations that had been made. In all these ways, the work the Foundation had supported exceeded expectations.

And then, as my father tells it, Sir John smiled pleasantly. He always did and said, “this is great son. Now, tell me what are our real results”?

I tell this story from time to time, and I get many different reactions. Some think it must have been discouraging to receive that kind of feedback, and I think Dad was deflated, initially.

But ultimately we took this simple question on board at the John Templeton Foundation. What are the real results of what we fund?

You see, Sir John Templeton created the John Templeton Foundation and the Templeton World Charity Foundation and the Templeton Religion Trust to make a difference in the world. With respect to character specifically, Sir John said, “it is my hope that more and more people worldwide will lead lives of happiness, usefulness and prosperity if we work continuously toward spiritual growth and a better understanding of the virtues by which” we want to live.

Sir John’s motivation for supporting research on character development came from the realization, as he writes in one of his first books The Templeton Plan: 21 Steps to Personal Success and Real Happiness, that his life would have been more useful had he fully understood and adopted the set of virtues and maxims he described in The Templeton Plan.

He therefore wanted to support work that would contribute to a world where individuals, institutions and communities are characterized by virtue and virtuous living. These are the real results that he had in mind.

In the next few minutes, I want to reflect on how we have tried to fund work that produces real results. And I want to acknowledge that we, funders, scholars and practitioners, still have work to do.

Let’s start by looking back. JTF’s investments in character development began with practical efforts to develop character in young people and to honor those who were committed to investing in character development. We supported essay contests for students to reflect on maxims that inspired them to live a life of virtue. We funded these programs with the thought that the experience of writing about what one believes would instill and reinforce a sense of virtue that would persist over the lifetime. We developed the Honor Roll for Character Building Colleges and Universities, recognizing that our educational institutions are places where character is instilled and that the cultivation of character in the school setting can be positive, if institutions are thoughtful about how their programs shape the character of the young people in their care.

For many years, we published an index that identified institutions, leaders and programs that were committed to developing character and virtue among their undergraduate students.

And then we moved on to begin supporting research on character and on character virtues. We funded projects that explored spiritual formation recognizing that spiritual development is an important aspect of character development and in 1997, we launched the Campaign for Forgiveness Research, our first substantive and extensive investment in empirical research on character development and practices that contribute to spiritual growth. The Campaign invested $10 million in research on forgiveness, supporting just 29 projects that we believe created the field of research on forgiveness. That was our first entrée into serious research on topics that many thought you couldn’t research.

Since the late 1990s, we have pursued programs and research to promote and understand character development over the lifespan. We contributed to the creation of the Purpose Prize, a prize program for retirees who pursue a second career dedicated to serving others by creating new projects, programs and businesses. The Prize, which is now run independently by the American Association for Retired Persons is really the opposite of retirement. We also initiated major research programs on gratitude, generosity and intellectual humility. Our funding influenced careers – if you’re given money to study generosity at a key moment in graduate school it can change the kinds of questions you ask – and our support impacted the researchers who studied these virtues.

-

Generosity. Illustration by Marina Muun.

One of the best reports I ever received was from a project that we supported in 2011. Called the Science of Intellectual Humility, this project funded nearly 30 scholars to explore various developmental aspects of intellectual humility. At the end of the program, the project leader asked those involved in the work to share broader reflections. Here is what they said —

“The process of researching a question is a humbling experience because it forces one to recognize that one possesses limited knowledge of a topic that is complex and nuanced. This has been my experience while researching intellectual humility. As a psychologist, I have found that philosophers and theologians in this area offer insightful perspectives that require me to reconsider the theoretical assumptions that underlie my work.”

“Outside of the lab, we have noticed ourselves thinking more about the limits of our own knowledge and being more willing to consider multiple vantage points in our daily lives.”

Now, I could tell you how this project, alongside other JTF investments in intellectual humility, led to a major increase in the number of papers published on intellectual humility. I could tell you how this project shaped the career trajectory of scholars involved in this project. I could tell you that we know more about the measures that they developed, and how we see references to intellectual humility cropping up in many different places including just recently in the Financial Times.

But at the end of the day, the real impact comes when these outcomes trickle down and result in changed hearts and minds. In that sense, the comments from these researchers are the real results. The researchers report that they are different because they were given the opportunity to study intellectual humility, and if they’re different, their families might be different, their classes might be different, their approach to research might be different and the circle of giving extends beyond there.