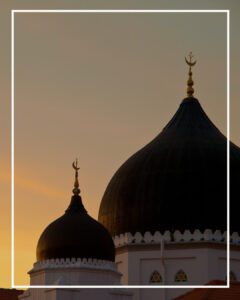

Photo source: Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic

When Stanford Law School Professor James Sonne founded the Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic in 2013, it was the first of its type in the country: a program that offered participating students full-time, lead-attorney experience representing a diverse group of clients who practice many different faiths. And it has been an inspiration. Other law schools, including Harvard, Yale, and Notre Dame, have since established similar clinics. After a decade of religious-liberty litigation, Stanford’s clinic has produced many valuable insights and illuminated the contemporary intersection of a robust American legal education, jurisprudence, and culture. Ultimately, these efforts aim to enhance human dignity and mutual respect for different lived experiences and perspectives.

Liberty in theory and in practice

The promise, history, and practice of religious freedom in the United States is complex. The First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States includes the words, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Freedom of religion is recognized as both a civil right—as per The Civil Rights Act of 1964 that prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin and freedom of religion—and a civil liberty (under the aforementioned constitutionally protected freedoms). Nevertheless, there are limitations.

Litigating these matters case by case is a massive undertaking. Students spend a full academic quarter at the legal clinic and don’t take any other courses. “This really gives us a unique opportunity to teach and to train them in not only religious liberty law and theory but also in the practical skills and professional skills that they need to be practicing lawyers,” says Sonne.

He adds that the work often requires creative solutions, intellectual curiosity, interdisciplinary thinking and planning, and a full embrace of supporting clients in their lives. Advocating for their clients through the lens of human-first problem solving is a salutary approach no matter what areas of legal practice or careers they choose. “The tools and judgment they acquire will serve them well in making a difference in the world,” says Sonne.

Indeed, law students from the clinic have appeared in local, state, and federal agencies, trial courts, and appellate courts nationwide. Alumni go on to top law firms, non-profits, and clerkships—including roles at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Making a case for human flourishing

The Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic has represented Buddhists, Christians (including Catholics, Evangelical and Mainline Protestants, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Orthodox, Quakers, Seventh-day Adventists, and Universalists), Hare Krishnas, Hindus, Muslims, Native Americans (who have many different belief systems), Orthodox and Reformed Jews, Rastafarians, and Sikhs. The legal disputes emanate from various practices and situations.

“I think in representing clients of all faiths—the cases, the projects we handle, involve matters of deep religious commitment and diverse religious commitments—and yet the principle that animates all our cases is one of human liberty and flourishing,”

says Sonne, who calls this a deeply human area of the law. “Across the cases that we work on and the clients we work for, we’re able to highlight in the lives of real people, in real cases, the ability and importance of each and every human person and communities to live out their faith with freedom and mutual respect.”

Practicing religion beyond the pews

Practicing religion beyond the pews

One of the Stanford Religious Liberty Clinic’s early standout cases involved “a homeless ministry that was located at a church, and the city in that case was trying to redefine the church’s activities as social service,” says Sonne. The city had a concern and interest in promoting public safety and in preventing crime, “But of course, our client looked at what they did in providing meals, clothing, prayer, and other forms of support as part of their religious faith – as a part of religious exercise.”

The clinic students were able to work on that case across several years, “All the way from the planning commission up to the Ninth Circuit. We ultimately secured a win at the Ninth Circuit that established the principle that religious exercise is not limited to what you might do in the pews on Sunday but really is something that should be protected and honored as an active form of engagement with your faith and in service of those in need,” says Sonne.

“The homeless ministry is a core part of that religious exercise for our client. And so, it’s an important principle to establish that religious liberty is not just the freedom to worship, but also the freedom to exercise your faith,”

says Sonne. There was eventually a settlement in the matter. “If there’s a way in which we can manage any countervailing interests in a way that still protects robust religious freedom, then we should be able to do that.”

Principal matters

Sonne says the cases are oftentimes about freedom, mutual respect, principle, competing visions of the world, “and how do you reconcile those? And how do you find a way to work, live, and serve others together?” Says Sonne.

“Some of our cases involve outright hostility, but a lot of them involve a failure of understanding, a failure to appreciate and to respect who our clients are, what their deep commitments are, and how we really can, in most cases, find a way to reach a solution that respects honors, accommodates our clients, while also fulfilling whatever the objective is that an employer might have or the government might have.”

The clinic was involved in a case “involving the ability of a death row inmate to have a chaplain of his own faith attend and be by his side at the time of execution in Alabama,” says Sonne. That practice was historically allowed for select Christian inmates in Alabama but not for those of other faiths. “We worked on that case and were able to achieve success in that case.”

He says, however, that the overwhelming majority of cases that the clinic works on are the ordinary “everyday lived experience of our clients,” says Sonne. For example, they represent a Seventh-Day Adventist client who was refused a job because of her religious observance of the Sabbath from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday.

In his work at the clinic, “What surprises me most is the range of scenarios and situations in which these challenges come up…And the many different situations affecting people in different ways,” says Sonne. “The principle of religious liberty for all protects everyone and their ability to choose for themselves, who they are, what life’s about, what comes next, and answer life’s deepest questions for themselves in freedom. And that core part of who we are as human beings in making those decisions is something of great importance and should be protected.”

Freedom in a rapidly shifting religious landscape

Freedom in a rapidly shifting religious landscape

A new Pew Research Center survey of American spirituality addresses previous research showing a decline in traditional religious beliefs and practices and those who attend religious services regularly. Yet 7 in 10 U.S. adults still describe themselves as spiritual in some way, including 22% who are spiritual but not religious.

We have a diverse, pluralistic society that looks at questions differently. Sonne shares that diminished religious literacy, greater diversity, government intervention, and bigger employers are all factors in the current landscape. “And yet, at the same time, there’s this common thread of humanity that we’re all in a journey, we’re all discerning these questions for ourselves and our families and our communities, and that common yearning that we have,” says Sonne.

In this era of political divisions and divisions in our broader culture, Sonne sees an opportunity in religious liberty and the law for bridge-building, consensus, and mutual respect.

“Something that I’ve been particularly proud of in our work is really drawing together people of different perspectives, of different backgrounds, of different faith traditions, or no faith for folks who aren’t religious,” says Sonne adding that this includes engaging clients across all faiths as well as teaching and training students who come from different perspectives and backgrounds. “Bringing people together to solve these problems for our clients, to really show a common humanity.”

Alene Dawson is a Southern California-based writer known for her intelligent and popular features, cover stories, interviews, and award-winning publications. She’s a regular contributor to the LA Times.

“Religious liberty for all, where some might see controversy or a problem, is actually a solution. If rightly understood, it brings down the temperature in these disputes. It provides a platform for mutual understanding and respect. That’s been beautiful to see fulfilled in our work.”

Freedom in a rapidly shifting religious landscape

Freedom in a rapidly shifting religious landscape