This piece is from the Templeton Ideas archives. It was originally published in 2021.

Hope is the seedbed of change. But it doesn’t always feel good.

Hope is the heartbeat of stories. The hero’s journey, great epics, and books that keep us reading well past bedtime all depend on hope. Without it, Harry Potter couldn’t face Voldemort. Jane Eyre couldn’t maintain her steely resolve for independence. Odysseus couldn’t endure a decade-long journey home.

While we recognize hope when we see it, it’s tricky to define. Most philosophers agree that hope requires belief and desire. To experience hope, you have to both desire something and believe that acquiring that thing is possible. (“I want to change the world, and I think it’s possible to make an impact.”) But desire and belief alone don’t create hope. There’s a third ingredient, the secret sauce, that helps explain hope’s power and potency—the kind of power that enabled Nelson Mandela to endure 27 years in prison, or Martin Luther King Jr. to dream of a more equitable world before it existed. So what is it?

Here’s where people disagree. Some philosophers argue that this third thing is trust in an external actor: a hopeful person must believe something outside of herself, like God or nature, is conspiring on her behalf. Others, like Michael Milona and Katie Stockdale of Templeton’s Hope & Optimism Initiative, say hope’s third ingredient is an emotional perception of reasons for action. In other words, hope has to include a perceived reason to move forward. A beginning runner who hopes to one day run a marathon must a) want to run it, b) believe she can run it, and c) see a reason to run it, whether that reason is physical health, mental endurance, or the 26.2 bumper sticker.

Why hope doesn’t always feel good

Belief, desire, and reason may seem like a feel-good recipe. But research and lived experience teach us that hope isn’t always pleasurable. This is because hope often occurs alongside deep fear and doubt.

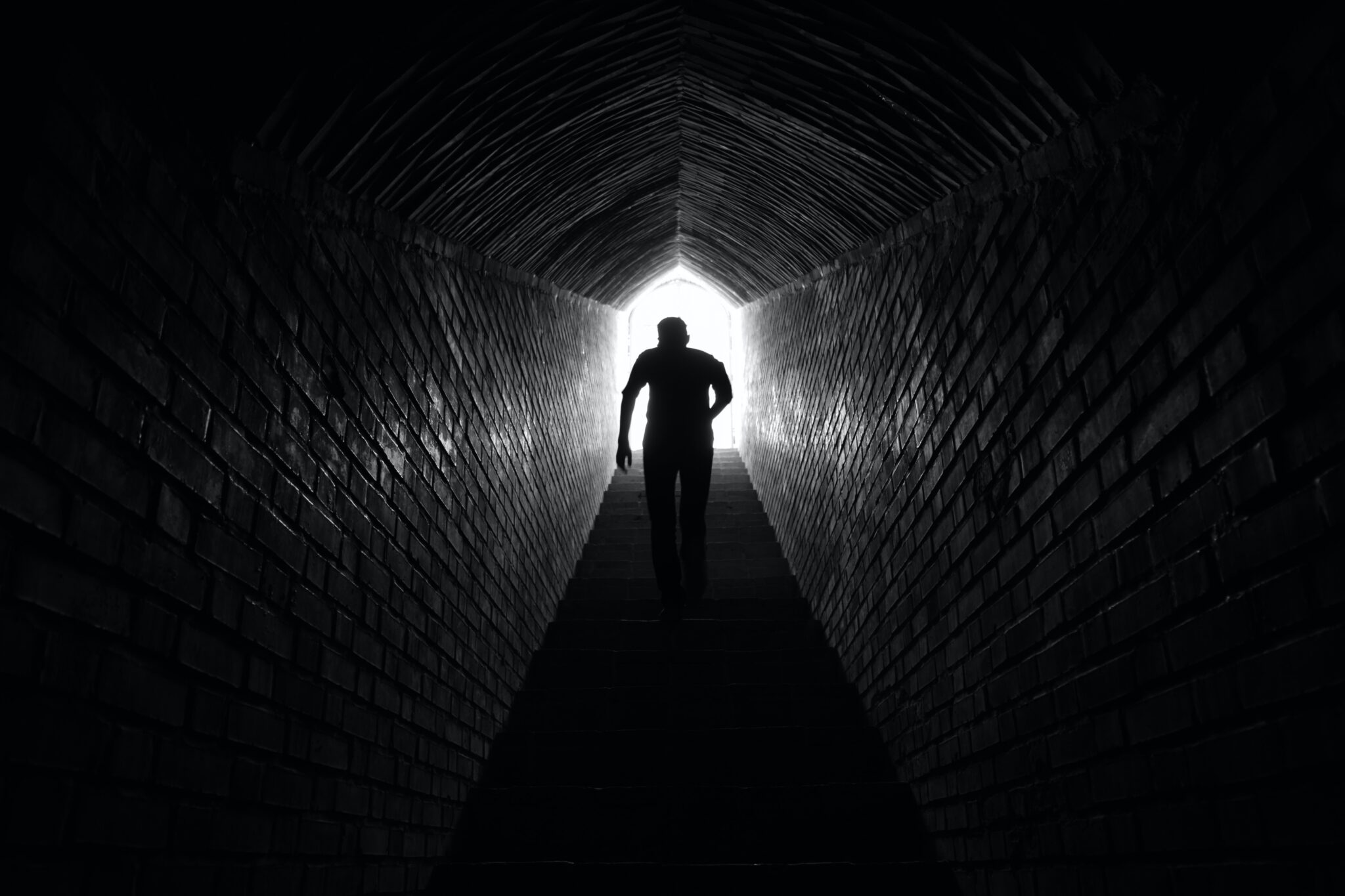

It’s possible to hold onto hope even when we’ve lost confidence—for example, we might hope for racial justice even when we aren’t optimistic that reform is near. Even when we hope with confidence, our longing remains laced with doubt. The more deeply we hope for an uncertain outcome (“I hope to one day be released from prison”), the more we fear that our hope won’t be realized (“I fear I will never be free”). The negative sensations of fear counteract, or at least temper, hope’s pleasant feelings. As Milona writes, “Uncertainty is the province of hope and fear.”

In the end, the only negative emotion that hope can truly rule out is despair. When we despair, we see no reason to move forward. As long as we continue seeing reasons to go on, hope survives. After decades in prison, Nelson Mandela was freed and returned home to reform his country of South Africa. In his autobiography he wrote about this durability of home amidst doubt:

“There were many dark moments when my faith in humanity was sorely tested, but I would not and could not give myself up to despair. That way lay defeat and death.”

We see this pattern over and over in the stories we love. Obstacles arise, chances may appear slim, fear may threaten to overcome the protagonist—yet as long as hope persists, so does our hero.

Hope’s motivational value

Because hope involves desire, it nudges us to think about means as well as ends. When we hope for something, we are motivated to bring about the object of our hope. In the case of our would-be marathoner, the hope of crossing the finish line makes her more likely to put in the work of training. Without hope that she can complete the race, she’s less motivated to change her diet, give up alcohol, and wake up early on Saturdays to run. Rather than tempting us to sit back and relish an imaginary outcome, hope prompts us to take action toward that end.

But wait, you might be thinking, might hope make us foolish and complacent? Can’t you still work toward change without hope, as in the case of activists who claim to be motivated by anger or bitterness?

In her 2019 speech, climate activist Greta Thunberg told world leaders, “I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. …I want you to act as if our house is on fire. Because it is.”

Thunberg was rejecting the kind of naïve optimism that soothes fear and paints a falsely rosy picture of the future. But her desire for people to panic isn’t necessarily incompatible with hope. Even people who take Thunberg’s advice and claim to work hopelessly toward reform don’t completely lack hope. They might not be optimistic that the world will adopt climate policies in time to save millions of species from extinction. But as long as they maintain the desire to make things better, the belief it is possible for them to do this, and a reason to do so, hope is at play.

That’s the good news about hope: even at its most abstract, such as a longing to live up to our convictions, hope has the power to galvanize us into action and bring about change.