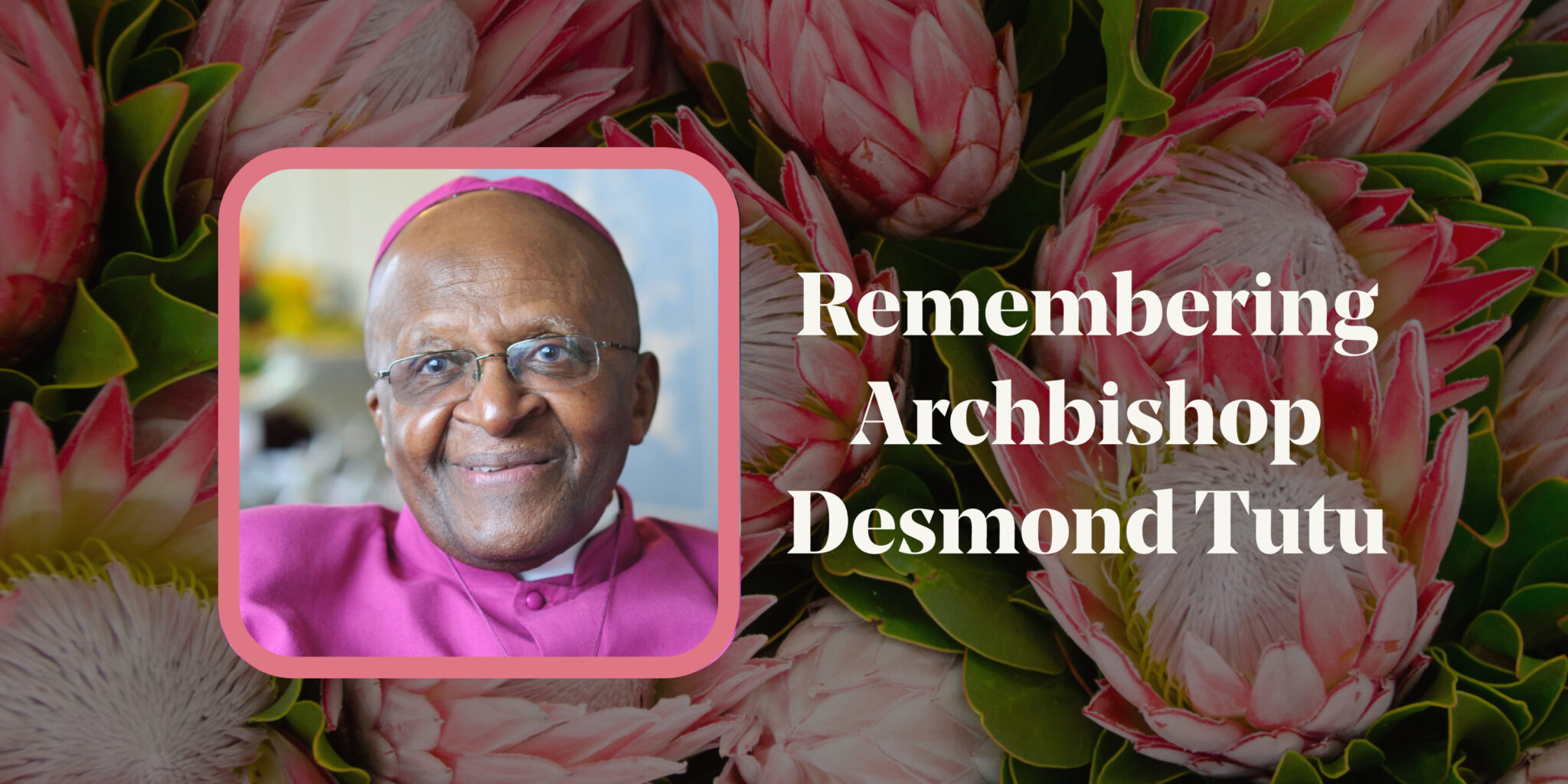

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who passed away the day after Christmas 2021 at age 90, is justly remembered and celebrated for his moral courage in protesting apartheid in South Africa. He was, as fellow Templeton Prize winner and personal friend the Dalai Lama wrote, a “true humanitarian” who worked to serve “his brothers and sisters for the greater common good.”

Yet he was also, despite the seriousness of his life’s work, extremely funny. Those who had the privilege of meeting him describe him as a bundle of joy—a playful, light-hearted, even impish spirit who spread the gift of laughter wherever he went.

This quality is abundantly on display in his interviews recorded for the Templeton Prize Lecture in 2013. Asked to speak on the traditional African concept of ubuntu, or togetherness, Tutu offers a rollicking and colorful retelling of the Genesis creation story of Adam and Eve.

First, he defines ubuntu as the essence of being human: that we become human through others, that “a person is a person through other persons.”

Then he offers an illustration by pointing to the Garden of Eden. “Adam was having the time of his life with the animals, and everything was good,” he laughs.

“But God said it is not good for that guy to be there alone. But he wasn’t alone. There were elephants, and giraffes, and whatever, and yet God said, he’s alone.” Tutu jokes that Adam rejected God’s offer of a companion from one of these animals— “Not on your life!”—causing the interviewer to laugh. Then he says,

“God put Adam to sleep and out of his rib produced this delectable creature, Eve, and Adam awoke and said, ‘Wow, this is just what the doctor ordered.’”

In addition to amusing the interviewer, Tutu uses this story to show that all humans require others to be fully human. He observes that we could not speak—we would have no language—without others. “I speak as a human being because I copied, I imitated, other human beings.”

“We are made for complementarity,” he says. “Adam had certain gifts, Eve had certain gifts. But it was only when the two made up what was lacking in the other that they became fully human. And that is the fundamental law of our being. Ubuntu says not, you are human because you think, you are human because you participate in relationship.”

When we do as God wants—to be humane, to honor the fundamental law of togetherness with one another and with him—God celebrates in heaven, Tutu says, doing a little dance of joy.

“I think most of the time,” he smiles, “God is laughing with us.”

-

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu at the Templeton Prize celebration at St. George’s Cathedral. Credit: Templeton Prize: Karen Marshall

-

Desmond Tutu Dancing at the 2013 Templeton Prize Celebration

-

Desmond Tutu and Heather Templeton Dill at the 2013 Templeton Prize Celebration

-

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, 2013