A look at the individual, social, and cultural reasons behind why we give.

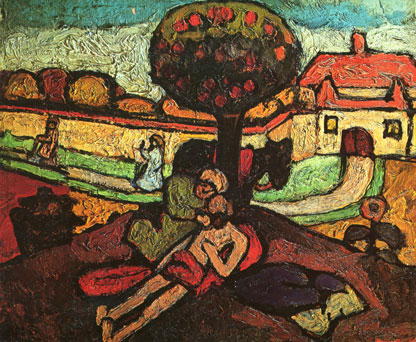

In the Biblical parable of the Good Samaritan, a man is besieged by robbers, beaten, and left for dead on the side of the road. Throughout the day, two travelers pass by—one of whom is a priest—but neither stop to help. Finally, a Samaritan comes down the road. Seeing the man in need, he treats his wounds, carries him by donkey to a nearby inn, and pays for his stay.

It’s a familiar story, so frequently invoked that we use “Good Samaritan” as shorthand for someone who acts generously. The Samaritan is the clear hero of the story. But here’s a question: Why didn’t the other two travelers stop? Might the Samaritan have possessed certain traits that encouraged his actions? Of course, we’ll never know the full story. But research shows that individual, cultural, and social factors influence our propensity to give to others—or not.

The University of Notre Dame’s Science of Generosity Project defines generosity as “the virtue of giving good things to others freely and abundantly.” Generosity doesn’t stop with financial gifts; we can also help others by sharing time, energy, material resources, and social connections. As it turns out, humans have given these good things throughout our history. Recent research points to a biological bent toward generosity, writes Dr. Summer Allen in a paper on the science of generosity prepared for the John Templeton Foundation. Giving activates the same reward pathways as eating and sex, an indication that generosity, which often benefits the whole community, is an evolutionary adaptation.

Along with our generous history, researchers have begun studying why we give. What are the factors that lead us toward—or away from—generous behavior?

Happier people give more

Whether inherent or cultivated, feelings of empathy, happiness, and awe can increase generosity.

Emotion researchers define empathy as “the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling.” This sort of imaginative sensing helps us put ourselves in another’s shoes. An empathetic person is more likely to experience a sense of oneness with the young man asking for spare change on the street corner, and therefore more likely to help him.

Like empathetic people, happier people give more to others. In a 2012 study, one group was asked to think of a time they purchased something for another person. The second group remembered a purchase they made for themselves. Not only did the first group report feeling happier, this group was also more likely to choose to spend money on others in a follow-up experiment, suggesting “a positive feedback loop between generosity and happiness,” writes Allen.

Feelings of awe also lead us to altruism. Whether spending time in nature, worshipping, or looking at a newborn’s face, elevating experiences tend to elevate our propensity to give. Participants in one study who marveled at a eucalyptus grove picked up more pens for the researcher who “accidentally” dropped them than the participants who only looked at a building.

Different groups display generosity differently

Male or female, religious or secular, rich or poor: identities play a role in how—but not necessarily how much—we give.

In a study of nearly 30,000 U.S. residents, those who identified as religious were 25 percent more likely to donate money to charity. Still, it’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions since the study relied only on self-reported giving. When it comes to volunteering and religiosity, a stronger correlation appears. Multiple studies show that religious individuals volunteer more than their secular counterparts. What’s more, attending religious services is a strong predictor of someone’s willingness to volunteer time and energy on behalf of others.

In another study using data from 3,572 American households, the tendency to give fluctuated among men and women. One gender isn’t more generous than the other, but the genders do display generosity in different ways. Men, for example, tend to adjust their giving based on tax incentives and income. They give more money to fewer causes, while women support more charities at lower amounts.

As far as financial standing goes, we might assume that more money equals more generosity. But it turns out, the equation is not quite that simple. Socioeconomic status plays a complex role in individual giving. Studies have contradicted each other, with some suggesting that poorer people are more generous and others finding just the opposite. What is clear is that, even more than income level, we’re influenced by the recipient of our charity. Whether we come from a high or low socioeconomic standing, we’re far more likely to help an individual with a specific need than an anonymous recipient.

Giving is socially contagious

Maybe our propensity to help out a specific person over an unknown beneficiary isn’t surprising. Generosity is an inherently social act, and our giving is heavily influenced by social pressure and expectations.

This is where the decision to give can veer from pure selflessness. Results from a range of studies confirms that people often give out of an expectation that they’ll receive some kind of return; out of a sense of being watched; or from a desire to raise their social standing.

However, the sway that social pressure holds over our giving can also be a boon. Generosity is socially contagious. The more generous your friends, family, and colleagues are, the more giving you’re likely to be. Fundraisers have used this social influence to their advantage. In an art gallery, a clear donation box partially filled with money caused patrons to give at a higher level. In a Costa Rican national park, visitors who learned the typical donation amount gave four percent more compared to visitors who weren’t told how much their peers gave.

There’s no telling exactly why the Good Samaritan stopped to help a wounded man while the other two travelers passed by. We can’t know if the priest was short on awe, or if the Samaritan’s altruism stemmed from his cultural identity. What we do know is that these factors can drive or deplete our generosity today, and thanks to ongoing research into why humans give, we know more about our giving tendencies than ever before.

Still Curious?

To read more on the science of generosity, click here.