You can’t see it, touch it, smell it, or taste it. It is like nothing else in the known world. It exists silently alongside ordinary matter, not interacting with it, but exerting a powerful effect. Its strange, almost imperceptible presence affects the very fabric of the cosmos—in fact, it holds creation together.

Though it sounds like a concept out of Avicenna or Aquinas, this strange thing is an object of intense study in modern physics: dark matter. While deep mysteries remain, thanks to new methods and approaches—some of which stretch the boundaries of science itself—astronomers are peeling back the veil to learn more about this invisible component of our universe.

Dr. Priya Natarajan, professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University, recently sat down with us to walk through new discoveries in a fascinating discussion called “Paradigms, Anomalies, and Discoveries.” In addition to her work probing dark matter, Dr. Natarajan is the leader of a John Templeton Foundation-supported project exploring the nature of inference in the physical sciences.

“Exciting discoveries are opening up ever new questions,” she says, “and those questions are now hitting up against the walls of the limitations of the ways in which we have posed these questions and the methods we have used to probe the universe.”

‘The Scaffolding and the Cocoon’: Mapping the Shape of Dark Matter

Though dark matter makes up roughly six times the mass of visible matter in the universe—that is, all the billions of galaxies and billions of trillions of stars that astronomers study through telescopes—we cannot detect it directly. We do not know what it is made of. All we know is that clumps of it aggregate, and these clumps are unimaginably massive.

Source: Sci-News.com

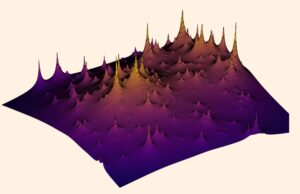

Dr. Natarajan explains that the only way to “see” dark matter is to infer its presence, as she has done by examining how concentrated clumps of dark matter bend light. These clumps create distortions in the real shapes of galaxies, like a cosmic funhouse mirror. She and her team have meticulously untangled these warped shapes to create the first detailed, high-resolution topographic maps of the dark matter that caused them.

“I’m obsessed with mapping in general and this process of epistemically mapping,” she says. “I believe mapping is knowing.”

The Collision of the Subjective and Objective

Her study of such numinous, elusive stuff has given Dr. Natarajan a unique view on the limits of scientific inquiry. It has also inspired reflection on how the practice of science could and should be changed. In the past, she says, the content and context of science were believed to be separate, creating an “artificial distinction.” She commends new ways of thinking about science that acknowledge the importance of context— who is asking the questions, in what institutions, with what values. “The very questions we ask in science,” she says, “has everything to do with values.”

The history of how radical ideas have been proposed, adjudicated, adopted, and accepted as fact by the scientific community shows the importance of ambient and structural factors. And the narrative of science is often “sanitized” to avoid showing the failures that define much of science.

“I think the context and content of science are deeply intertwined,” she says. “Who comes up with the radical idea, how they pose the question, what resources they have to pose it – all play a role in how an idea gets accepted as scientific fact.”

This process suggests that an update is needed to the influential view put forward by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, who argued that science advanced by sudden revolutions in ideas—paradigm shifts: from a geocentric to the heliocentric model of the solar system, from Newtonian physics to relativistic and quantum mechanics. The advance of knowledge is more a combination of revolution and evolution, argues Dr. Natarajan.

While some aspects of science need revision, and its progress is “provisional and uncertain,” she notes, science remains “the best way forward for understanding nature and our place in the scheme of things.”

Still Curious?

Explore more of the great minds from across the sciences and humanities in our other Speakers Series conversations and learn more about Dr. Priya Natarajan’s work on Understanding the Nature of Inference: Discerning Deeper Correlations and Causation.

- Watch psychologist Amrisha Vaish on the emergence of forgiveness in children.

- Watch psychologist Dr. Tania Lombrozo discuss the important and complementary differences between thinking about science and thinking about religion

- Watch Ford Foundation president Darren Walker on why hope is the oxygen of democracy.

- Watch geneticist, physician, and 2020 Templeton Prize winner Francis Collins speak about the discovery that filled him with awe

- Watch physicist Alan Lightman of MIT describe how he found transcendental meaning in the bottom of a boat.

- Watch biologist Stuart Firestein of Columbia University share an exclusive early draft of a book he’s writing which argues that science invented optimism.

- Watch economist Tyler Cowen of George Mason University explain how to radically accelerate the process of scientific discovery.