A monk, an umbrella, an essay — and many changed lives

When he sent in his submission for the John Templeton Foundation’s 2004 essay contest, August Turak had already been a successful entrepreneur and CEO, a mid-1970s student of Zen Buddhism, a mentor to college students, and a failed amateur skydiver (one attempt, ankle shattered). What he was not, in any sense of the term, was a published writer. A betting person might have given him rather long odds to win the $100,000 prize for the best essay on the “power of purpose” — the contest was open to professional writers and already-published works. Indeed, when the Foundation’s board members contacted him that September to tell him he’d won, the conference call took on a slapstick air with everyone talking at once. “At first I was sure it was my buddies playing a prank on me,” Turak recalls. But it was no prank. Turak’s essay, “Brother John,” had been judged the top submission, and that September, Turak was feted at an award ceremony at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York City, accompanied by the subject of his essay, Brother John, a 65-year-old Trappist Monk from Mepkin Abbey in South Carolina.

Turak’s essay described a visit to Mepkin Abbey in 1997 during the midst of a season of personal despair that he considers his two-year “Dark Night of the Soul.” His skydiving accident made him face his mortality for the first time, and triggered a full-blown crisis of purpose. “I realized that I had been on a so-called spiritual path since I’ve been in college, but now when I really needed it, all I cared about was what the doctors had to say,” Turak says. In the midst of that depression, Turak got a call from a Duke student he’d once mentored, saying that he was spending his summer as a monastic guest at Mepkin Abbey. Intrigued, Turak himself made inquires about visiting the abbey.

It was on one of this visits that Turak stepped out of the abbey on a rainy December night and encountered Brother John, waiting with an umbrella in case any of the monastery guests had forgotten their own.

Brother John was one of the busiest, most competent, and hardest working of the Mepkin monks, serving as a foreman for the work required to keep the abbey and its associated businesses running. That such a man also thought nothing of missing the abbey’s Christmas party in case a few monastic guests needed help staying dry was for Turak both a gift and a challenge bordering on affront. “On one hand,” Turak wrote in the essay, “he represented everything I had ever longed for, and on the other, all that I had ever feared.” Turak found that his fear was the fear of trying and failing — of attempting to devote one’s life to love and service and then falling short: “I was terrified that if I ever did decide to follow the example of Brother John, I would either fail completely or, at best, be faced with a life of unremitting effort.” But as Turak reflected, he came to realize that Brother John’s humble service, far from being an affront, was an invitation to take risks that leave room for the miraculous.

It took some time, but Turak began working to take such risks and make such room — eventually selling off his businesses to be able to dedicate himself to speaking and mentoring college students, studying theology, and spending time as a guest at Mepkin. Along the way, his dark night of the soul finally lifted.

MONKISH BUSINESS

After it won the Templeton essay prize, “Brother John” took on a life of its own. It was anthologized in The Best Catholic Writing 2005 and The Best Christian Writing 2006. More importantly, it galvanized Turak as a writer. Within a few years, Forbes published his observations on the business practices of Mepkin Abbey, which Columbia Business School Press later published in a book titled Business Secrets of the Trappist Monks: One CEO’s Quest for Meaning and Authenticity. Turak took the prize money and donated it to charity — part to the monastery and part to enable his own expanded work in mentoring and public speaking through the Self Knowledge Symposium Foundation, which he founded.

More than a decade after it was initially published, Turak still receives messages from readers who have found the essay helpful during times of personal suffering. “Every time I get one I find it very humbling and very beautiful — that something that I wrote is able to help people. But if it was helping dozens, why couldn’t it help hundreds or thousands?” Turak wonders.

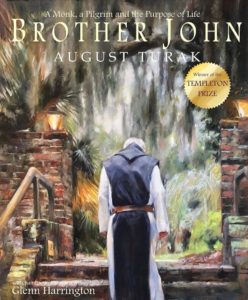

To address this enduring interest, Turak approached a publisher to release an illustrated edition. He worked with painter Glenn Harrington, who traveled to Moncks Corner, South Carolina to spend several days observing and photographing Mepkin Abbey’s monks. Harrington produced a suite of 23 impressionistic paintings that portray vivid scenes of monastic life. The monks — always depicted from behind — are shown moving through buildings and along palmetto-lined garden paths. (Mepkin Abbey occupies an estate and gardens donated by heiress Clare Booth Luce.) The rear view seems a nod both to the intentional anonymity of the monks’ vocation and an invitation for the reader to quite literally follow in their steps.

THE FAITH TO GO INTO THE UNKNOWN

Brother John: A Monk, a Pilgrim and the Purpose of Life will be published this October. Turak is hopeful that the book can reach a new audience of spiritually hungry readers. To further share the lessons of this community, he has worked with corporate partners to adapt Business Secrets of the Trappist Monks into a curriculum for institutions to help employees explore and act upon their own senses of purpose.

“When I was in business I enjoyed being able to plan something out and see it all happen just as I predicted it would,” Turak says. “But I never had a plan for my life. I said what I have from our life is a mission. And now when I look back I see that my whole life is going off according to a plan. It’s like Kierkegaard said: the problem with life is that it must be lived forwards but only understood backwards. What the monks have that very few of us have — but that we all need — is the faith to go into the unknown.”

STILL CURIOUS?

Order the new illustrated edition of Brother John: A Monk, a Pilgrim and the Purpose of Life

Learn more about August Turak’s ongoing work through the Self Knowledge Symposium Foundation.