This story is Part II of a new series on worship. Read Part I.

“The astonishment is all in the being here.” – Kathryn Schulz

Kathryn Schulz’s memoir Lost & Found is a profound meditation on grief, love, and the astonishment of being alive. Schulz is a secular Jew. But her atheism doesn’t preclude her from moving through the world with a sense of awe and wonder. Much of the memoir reads like a song of simultaneous praise and lament.

For Schulz, paying close attention to the world and our place in it is a way to honor and celebrate the singular life we each receive. “Our crossing is a brief one, best spent bearing witness to all that we see: honoring what we find noble, tending what we know needs our care, recognizing that we are inseparably connected to all of it, including what is not yet upon us, including what is already gone,” she writes. Her practice of bearing witness might be categorized as a secular form of worship. And while worship is not a word typically associated with an atheist worldview, philosophers believe it has a place in modern, secular life—indeed, that it adds beauty and richness to any life.

Rituals for the unbeliever

As a child, Saul Smilansky’s daughter developed a ritual for walking down the street. She stepped on certain sidewalk patterns and avoided others, a playful practice that made an ordinary walk more interesting. Smilansky, now a philosophy professor at University of Haifa, soon joined her. Today, his daughter grown, he still finds himself following these patterns. This basic act of attention connects father and daughter across years and miles. And while this is a trivial example of non-religious rituals, Smilansky argues that its mundanity is exactly the point. There are “minimalistic requirements,” he writes, “and easy benefits, of attitudes and practices of devotion that can be characterized as quasi-worship, without any religious assumptions.”

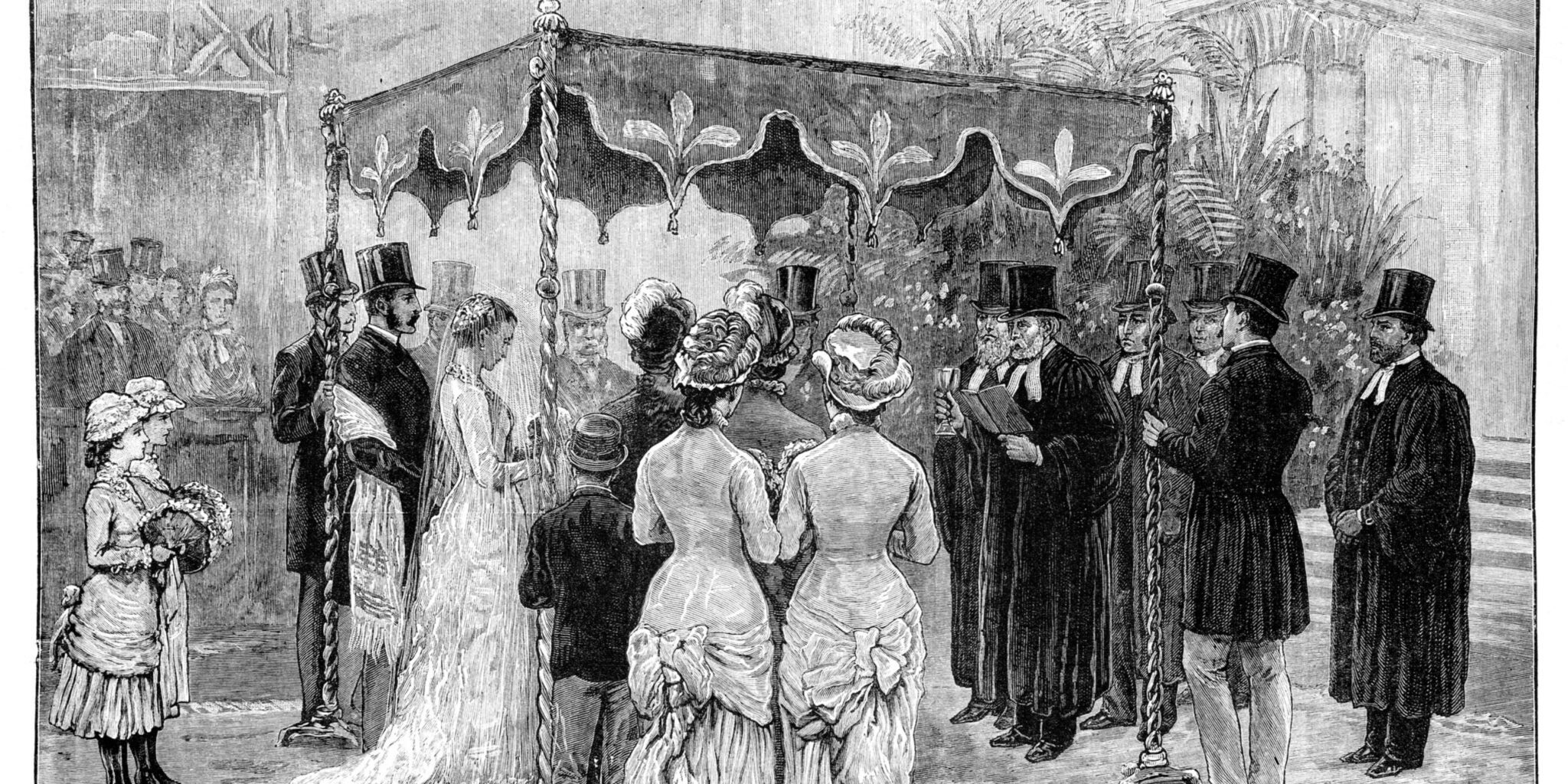

Smilansky is interested in what he dubs “atheistic worship.” He suggests that incorporating rituals of devotion into a life otherwise devoid of religion can foster gratitude, wonder, and connection. Secular rituals, he says, can provide similar benefits to what divinely-focused worship offers. “Secular Jewish atheists regularly engage in practices which closely resemble and indeed follow religious ones, such as weddings and prayer in high holidays.” Despite a lack of a divine object, these practices are still meaningful and still contribute to a Jewish sense of identity. He points to Japanese culture as another example, where traditional and repetitive gestures—from tea ceremonies to Sumo matches—are seen to have worshipful elements. And across the world, atheists can and do participate in “systematic, complex, widespread acts and rites of devotion and worship.” One only has to look as far as the Superbowl or an English Premier League match to realize that sports teams and athletes enjoy their own kind of worship. Similarly, many atheists find value in honoring and learning from great moral heroes.

A longing for ritual and awe persists in secular culture. Atheistic forms of devotion can offer experiences akin to religious worship. Whether people attend sports games or enact private rituals, secular worship offers a way to connect, celebrate, and tap into wonder.

“Atheists cannot worship God, but they can worship beauty, art, morally heroic people, the memories of the good, and so on,”

Smilansky writes.

By doing so, they can also enjoy some of the benefits that the devout receive through more traditional forms of worship. Atheistic worship will naturally be of a more subdued variety than in theistic traditions—people are unlikely to apply the same level of obedience and subservience to, say, Nelson Mandela as the devout would apply to God. Yet atheists who participate in rituals and acts of devotion might discover that secular worship helps them attend to their inner world, foster gratitude, and connect to others in meaningful ways.

Liturgy for hopeful skeptics

For those who are not atheists but also not ready to whole-heartedly assent to the existence of God, liturgical worship can help them test-drive belief. In doing so, they can experience a deeper level of hope, says Andrew Chignell of Princeton University.

Chignell defines ordinary hope as a desire for something plus the possibility–however remote–that the desire could be attained. One could hope that extraterrestrial life exists, for example, and believe such existence is remotely possible. But deep hope, which Chignell calls “tenacious and life-structuring,” requires firm commitment to both the real possibility of something and the strong desire that it be fulfilled. Kant said that a firm commitment to the real possibility of God’s existence was the “minimum of theology” for genuine religion.

So what does this mean for those who lack this firm commitment? If deep hope is a key element of a meaningful life, can agnostics still access it? Chignell believes they can, and that embodied, liturgical worship is the way. “Liturgy is a place where people who don’t feel that they believe or accept might participate in the liturgy, and might do so with a kind of intentional movement upwards,” Chignell says. In other words, liturgy and embodied practices can help agnostics sense what it would be like if a religious belief were true. Liturgical worship allows them to inquire, discern, test out beliefs. For the hopeful skeptic, liturgy might move them toward acceptance or even belief.

The human impulse to worship extends beyond the walls of religious structures. While secular worship naturally holds a narrower scope than worship directed at the divine, its potential to create a richer life remains. For the atheist, agnostic, and wishful believer, forms of devotion are still available outside of religious traditions. And not only are they available, they might just be essential to a life well-lived.

Annelise Jolley is a journalist and essayist who writes about place, food, ecology, and faith for outlets such as National Geographic, The Atavist, The Rumpus, and The Millions. Find her at annelisejolley.com.