In November of 1997, His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew—the spiritual leader of the Eastern Orthodox church—hosted an environmental symposium that would make history.

At an Orthodox church set in the palm-fringed foothills of Santa Barbara, California, with the Pacific spreading below like an ultramarine altar cloth, the patriarch spoke to an audience of environmentalists, politicians, and indigenous leaders. He looked then much as he looks now. He wore simple black vestments and a white beard cascading to his chest. His gaze was gentle behind gold-rimmed glasses. Speaking in careful English—one of seven languages he speaks fluently—Bartholomew affirmed his church’s call and commitment to protecting the natural world.

Then, in a sentence that would quickly wing across the world through newspapers and broadcasts, the patriarch named the connection between environmental destruction and moral failing. “To commit a crime against the natural environment, against the natural world, is a sin,” he said, pausing to lift his eyes to his audience.

With this statement, he drew a direct link between religious obligation and environmental care—the first time such a connection had been made by a figure of his authority on this kind of public stage. It was a revolutionary declaration that reverberated across religious and secular communities alike—a “daring revision of the Christian perspective of sin,” as Rev. Dr. John Chryssavgis, Archdeacon of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and advisor to the patriarch, described it in the biography Bartholomew: Apostle and Visionary.

In this historic speech, the patriarch presented environmental care as a moral and spiritual imperative. More than policy change, he argued, humanity needs a spiritual conversion.

“Excessive consumption may be understood to issue from a world-view of estrangement from self, from land, from life, and from God,” he said.

Only by remembering our interdependence can we heal the damage caused by greed, exploitation, and disconnection.

His words echoed the Orthodox understanding of sin: not as mere moral missteps, but as relational rupture. By naming pollution and deforestation and reckless extraction as sins, Bartholomew underscored the relational breakdown at the heart of the issue, both among people and between people and the earth.

The Santa Barbara symposium was, Chryssavgis wrote, the first time a religious leader connected environmental abuse with sin. But for Patriarch Bartholomew—who is now affectionately known as the “Green Patriarch”—a commitment to ecological care preceded the symposium by many years, and has only deepened in the decades since.

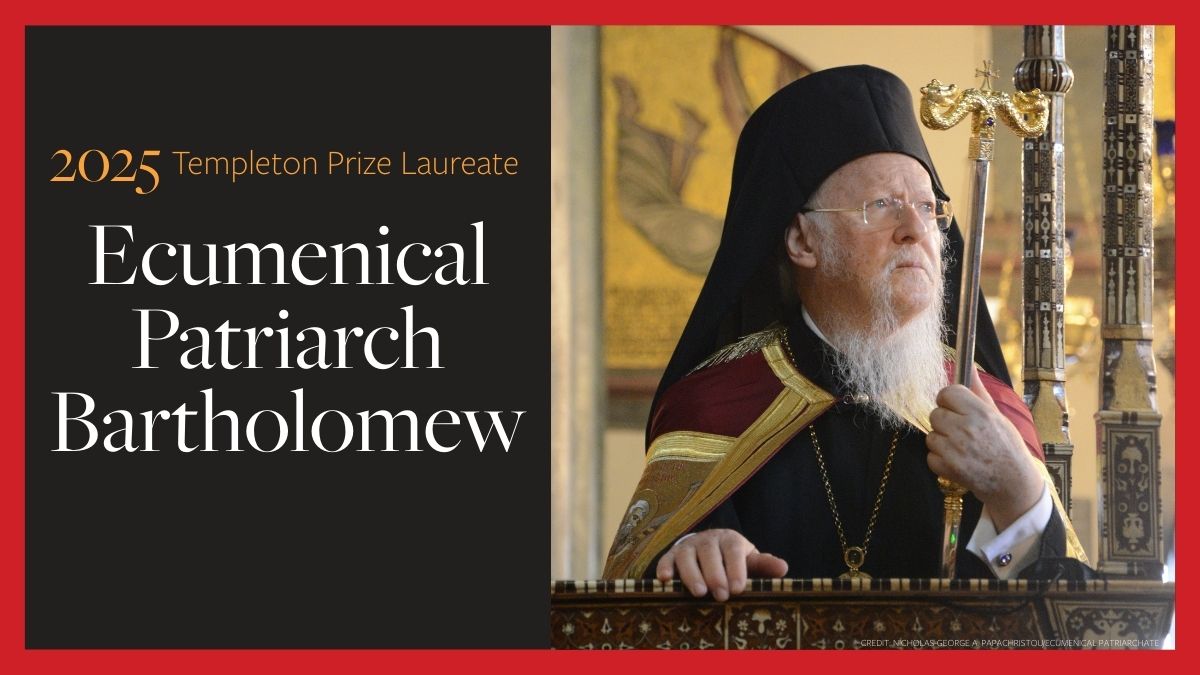

The recipient of the 2025 Templeton Prize, His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew is one of the longest-serving patriarchs in Orthodox history. He is the 270th direct successor of Saint Andrew the Apostle, the first fisherman called by Jesus to leave his nets behind and become a disciple. More than 300 million Orthodox Christians around the world look to Bartholomew as their spiritual leader.

Before he was elected ecumenical patriarch in 1991, before he took his vows and was ordained to the priesthood, Bartholomew was called Dimitrios. He was born on a leap year—February 29, 1940—in a small village on the island of Imbros. As a young boy, he helped the village priest at the altar or served as cantor during services. Diary entries from his teenage years show a young man already devoted to God and driven by a spiritual mission.

It was on Imbros that Bartholomew’s love for the natural world flourished. The island marks the westernmost point of Turkey, surrounded by the cerulean waters of the Aegean. His village was sustained by olive oil production, and olive groves spread across the landscape. Oleander bloomed wild on the hillsides where sheep and donkeys roamed. As a child, he would wander through his grandmother’s garden, which grew lush with chrysanthemums and roses. But while Bartholomew’s reverence for God’s creation began in a particular place, it expanded to include the planet as a whole.

“The Ecumenical Patriarch—he loves life. And life is everything around us,”

says Father Alex Karloutsos. Karloutsos is a Greek Orthodox priest who has served as a liaison with heads of churches, U.S. presidents, the Congress, state officials, and human rights groups. In 1994 Bartholomew named Karloutsos Protopresbyter of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the highest honor available to a married clergyman. The two have remained friends and collaborators in the decades since, connected by their shared commitment to the church and His All-Holiness’s service to the Mother Church of Constantinople.

On their walks together, Bartholomew often pauses to admire a plant or a flower, noting the contrast of its colors. “He sees an animal, and there’s a hugging of the animal,” Karloutsos adds. In this way, Bartholomew calls to mind Francis of Assisi, the saint celebrated for his deep love of all creatures. The patriarch’s affection for animals even prompted friends to give him a donkey one year for his birthday. His response, upon opening the card with a photo of his new companion, was delighted laughter.

The list of the patriarch’s professional accomplishments could fill a book. He has met with popes, presidents, and queens. He’s the recipient of more than 85 honorary doctorates. He was named one of Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” in 2008, and has been recognized on numerous international stages. This is a man who joked with Jane Goodall and shared a long friendship with Pope Francis, someone whom former president Joe Biden called “one of the most Christlike men I have ever met.” Yet for all these accolades and superlatives, the quality that people are quickest to speak of is his humility.

When 60 Minutes correspondent Bob Simon met the patriarch in Istanbul in 2009, he wondered how to properly address him: “As Your All-Holiness? As Patriarch? As Ecumenical Patriarch?”

Bartholomew laughed. “The official title is ‘Your All-Holiness,’ but for me, Bartholomew is enough.”

This humility is something Karloutsos noticed upon meeting the patriarch in 1983. Recalling their first interaction, Karloutsos says, “It was amazing because he, of course, speaks seven languages. [But] the ultimate language with which he communicates is love and humility.” This gentleness immediately sets people at ease in his presence. “You’re not overwhelmed by his intelligence, but he illuminates—he enlightens—the world around you when you’re in this midst.”

Like all of his predecessor patriarchs, Bartholomew calls Constantinople—now Istanbul—his home. Once the geographical hub of Christianity, today Istanbul is over 99 percent Muslim. It is a bridge between worlds, the meeting place of Islam and Orthodox Christianity, and a fitting home for a patriarch celebrated for interfaith dialogue and bridge building.

Much of his tenure as ecumenical patriarch has been devoted to promoting reconciliation and relationships among diverse faiths. He’s known for fostering cooperation within the Orthodox community as well as interfaith dialogue across religious lines. Bartholomew has traveled more than any other patriarch in history—well beyond international meeting grounds like the UN and into places such as Libya, Israel, Syria, Egypt, and Qatar—earning him global respect and opening doors to establish relational bridges where no one had before.

Despite his profound intellect, the patriarch’s curiosity and humility draws people out and invites conversation. Chryssavgis emphasizes Bartholomew’s “capacity and willingness to learn,” and his “openness and readiness to dialogue.” The patriarch approaches the world with a wide embrace, seeking connection and conversation from a place of love rather than mistrust.

Addressing Orthodox Christians in a pastoral letter, Bartholomew called upon churches to adopt a similar posture of engagement. “Whoever believes that Orthodoxy has the truth does not fear dialogue, because truth has never been endangered by dialogue,” he wrote.

While climate change sits at the top of public consciousness today, Bartholomew’s activism began long before most religious communities had taken up the mantle of environmental care. It is both the longevity of his commitment and his cross-disciplinary approach that sets him apart. From the start of his tenure he’s seen science and religion as compatible, even complementary, partners in the fight to protect our planet.

For the patriarch, it is a false choice to separate science and religion, particularly when it comes to protecting our shared home. In the same way, he resists prioritizing spiritual matters at the expense of material ones. Just as with interfaith reconciliation, he approaches environmental activism with his arms open wide.

The Orthodox Church, says Chryssavgis, is often perceived as focusing on spiritual matters to the neglect of the material world. But for Bartholomew, “praying for and protecting the environment reflects a worldview that is part and parcel of Christian thought and spirituality.” Love for God and love for God’s creation should go hand-in-hand, each enriching the other.

As Bartholomew once told Chryssavgis,

“The environment is not a secular or fashionable issue. It is at the very heart of what matters for the God who created our world and who assumed flesh to dwell among us.”

Bartholomew embodies the kind of reverence for the world that Dostoyevsky writes about. In The Brothers Karamazov, Father Zosima tells his listeners, “Love all of God’s creation, both the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light. Love animals, love plants, love each thing. If you love each thing, you will perceive the mystery of God in things.”

The belief that God’s mystery and love permeates the material world hearkens back to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, formalized in Constantinople in 381. The Creed, from which Orthodoxy draws its foundational beliefs, opens with these words: “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.”

All things visible and invisible—or, one might say, material and spiritual. The spiritual life should lead one deeper into care for this earth, according to Bartholomew’s theology. All of life was created by a loving God, and therefore all of life—from donkeys to olive trees to children to the sea—is good and worthy of our care. It’s a world shot through with mystery and love, a world that, in the patriarch’s words, “contains seeds and traces of the living God.”

Patriarch Bartholomew’s humility, advocacy on behalf of the natural world, and peacemaking work all conspire to create a powerful “theological witness,” to borrow the words of Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams. This witness extends beyond the bounds of the Orthodox Church to reach the world at large. His patriarchate bears witness to the beauty of repair and reconciliation, both between diverse communities of people, and between people and the planet we call home.