Is it possible to ‘see’ the divine in nature? Many think so. It’s suggested that, perhaps after long immersion in religious practice, some are able to detect meaning and significance, and even the divine, in the world we observe around us. While I might look out of the window and see a sunset, others, looking at that same view, are overwhelmed by the glory of God. There are those who believe they can see divinity in the sweep of the starry heavens and the petals of a wildflower, and hear it in morning birdsong.

Do such experiences involve the detection of meaning, significance and divinity that’s really there, or is it a matter of our projecting meaning and significance on to a reality that, objectively speaking, it entirely lacks? And how can we tell which of these two things is going on?

If we are detecting meaning and significance that’s there, independently of us, how do we do it? One possibility is that the detection takes place via some additional sense – a sixth sense, as it were – that works alongside our more familiar senses of sight, touch, smell, hearing, and taste. However, if such experiences of divinity are delivered via an extra sense, why do the other senses also need to be employed? When it comes to experiencing divinity in nature – in a beautiful sunset or the song of birds – observation via our more familiar senses seems essential. You need to see sunset and hear the birdsong to experience the divinity. But if the divinity were detected by sixth sense, you would be able to detect it anyway, even while blindfold and wearing earplugs.

This suggests a different way in which we might detect divinity in the world around us: detecting divinity is a matter of correctly interpreting what our other senses deliver. Perhaps seeing God in nature is more like seeing the baby in fuzzy ultrasound images.

While an untrained observer of such images may detect nothing, a skilled reader can clearly see the baby. Their ability to observe the baby in the shifting patterns of dark and light on screen is a matter of their being able correctly to make sense of or interpret what they see.

If this is what seeing meaning, significance, and even divinity in nature involves, it would also be a matter of detecting what’s really out there. There really is a baby in the womb of the woman being scanned, and the skilled ultrasound scanner reader can see it there amid those shifting, fuzzy blobs; there really is meaning and divinity in that sunset, and a suitably sensitive observer can find it there amid the shifting shapes and colours.

Many religious people do seem to understand religious faith in part in terms of a way of seeing reality that makes sense of it. Alister McGrath, for example, says ‘Religious faith helps me make sense of the world by giving me a way of seeing reality which affirms both its intelligibility and coherence’. (my italics)

But is that what’s going on? Some will suggest that seeing the divine in nature is much more like seeing the canals on Mars. In the 1870’s the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed Mars through his telescope. The image he saw was fuzzy, but Schiaparelli became convinced that he could detect a system of canals carved into the planet’s surface.

Other astronomers joined in, confirming the existence of Schiaparelli’s canals. Further details were added, including black spots at the canal intersections. Eventually, detailed maps were created. Theories were also developed to account for what was observed. The astronomer Percival Lowell, whose sketches of the canals can be seen below, proposed that the canals were a series of ancient aqueducts designed to funnel water from the polar caps to irrigate the otherwise arid surface.

-

1877 map of Mars by Giovanni Schiaparelli

-

Illustration from Percival Lowell's Mars and its Canals, 1906

Of course, the canals did not exist (this was confirmed by Mariner fly-by in 1965). The suspicion, of course, is that those who claim to ‘see’ meaning, significance, and divinity in the world are similarly seeing something that’s not really there.

So how can we tell which of these things is going on? Are we detecting real significance and meaning in what’s before us, or merely projecting that meaning and significance into what we see?

When it comes to ultrasound images, we can confirm whether someone really is accurately detecting what’s there. If the ultrasound operator claims to see a baby in a particular position, we can, quite independently, check their claim is correct. Perhaps they think they’re looking at a hand, when in fact it turns out to be a foot. We can now similarly check what’s actually on the surface of Mars. However, no such independent check is possible when it comes to those claiming to experience the divine in nature.

Of course, the religious can point to considerable agreement among those who have experienced the divine about what it is that they’ve experienced. And it’s true that this agreement could be explained by them all observing the same thing. However, the agreement could also easily be a product of others factors – including the power of suggestion and the fact that we humans are prone to certain sorts of illusion. There was, after all, considerable agreement among those astronomers who saw Martian canals about the patterns of lines they observed.

Of course, just because we cannot independently check whether what those who claim to experience the divine in nature are detecting something that’s objectively there, doesn’t establish that they’re not detecting something that’s objectively there.

Still, one reason why we might be particularly suspicious about such experiences is that we know we humans are, in fact, prone to over-detecting agency in nature. An agent is someone or something (such as a human, a dog, an alien) that has beliefs and desires on which they may act. We are prone to see significance, and in particular, agency where in truth there is none. Claims about sightings of ghosts, spirits, fairies, and aliens are regularly debunked.

One of my favourite examples is provided by psychologist Chris French, who was employed on the Haunted Homes ghost-hunting TV show to provide a more skeptical view. The team investigated on old building in the dark and heard and recorded what they believed was a sneeze. The sound of this ‘sneezing ghost’ was later broadcast. What wasn’t broadcast was that when the site was revisited next day an automatic air freshener was discovered where the ghost was heard and which emitted the same ‘phffft!’ noise. An agent was detected where in truth there was none.

We’re also quick to posit extraordinary hidden agency to explain what we otherwise struggle to explain. When we couldn’t explain why the planets moved in the peculiar way they do (the retrograde motion of Mars, for example) we supposed they must be agents – gods. When we could not explain why plants grow in the spring, we attributed this to the activities of nature spirits.

One example of our proneness to over-detect agency is provided by pareidolia. Pareidolia is the tendency to find patterns and significance in random stuff.

In particular, we are able to find human, animal, and other faces where in truth none exist. Stare up at passing clouds, or into the embers of a fire, and you will quickly start to find faces.

As the philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) notes: ‘There is a universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves… We find human faces in the moon, armies in the clouds.’

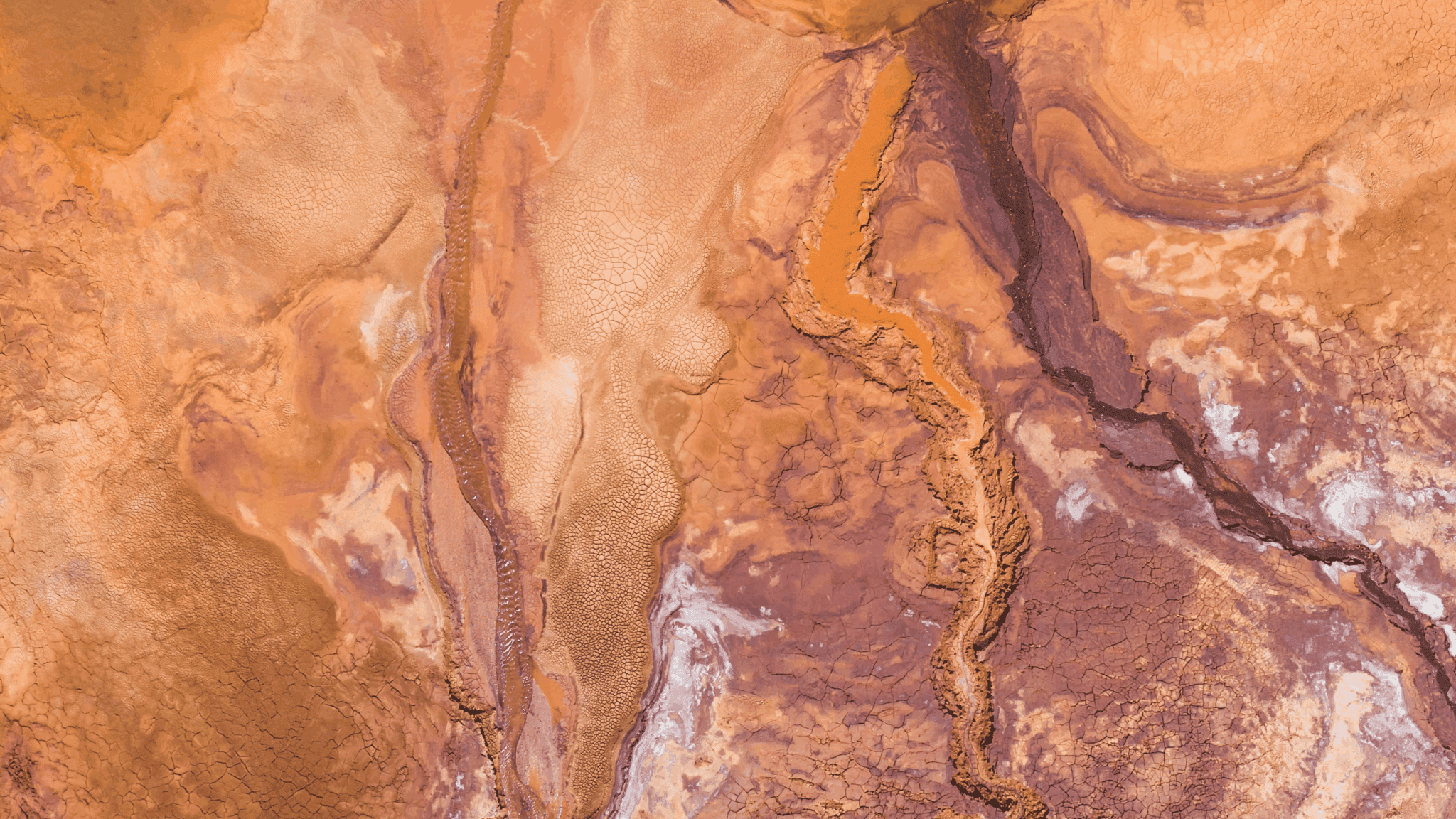

We can, for example, find a face in the bark of a tree or a desert landscape.

A striking illustration of this tendency is The Face on Mars. In 2001, NASA’s Viking Orbiter 1 spacecraft circled Mars taking photographs of the planet’s surface. One photograph of the Cydonia region soon became famous, as it seemed to reveal a huge reptilian-looking face some 800 feet high and almost two miles long.

Many were convinced this ‘face’ was a relic of an Ancient civilization – the Martian equivalent of the Great Sphinx of Giza. However, later images revealed it was just a hill that, when lit a certain way, coincidentally looked face-like.

In fact, the Face on Mars was really a product of two things. First, if you take enough photographs of random patterns, such as those thrown up by the Martian landscape, eventually, just by chance, something face-like will appear. Similarly, given millions of bits of bread are toasted each morning, it’s almost inevitable that one or two will appear very face-like. Second, pareidolia: we have a tendency to ‘see’ faces in such noise anyway. One scientific study concluded: ‘Our findings suggest that human face processing has a strong top-down component whereby sensory input with even the slightest suggestion of a face can result in the interpretation of a face.’ Put these two things together and the Face on Mars and the Nun in a Bun – a cinnamon bun that looked like Mother Teresa – are easily explained.

-

Face in a Tree

-

The Guardian of the Badlands, Alberta, Canada

-

The Face on Mars, NASA/JPL

-

Nun in a Bun

However, while we’re certainly prone to over-detecting agency – seeing ghosts, spirits, and even gods where there are none – pareidolia doesn’t seem to provide the right explanation for someone seeing God in a sunset. With pareidolia, we’re dealing with examples of one thing resembling another. That Martian hill looks like a reptilian face. That bun looks like Mother Teresa. The religious person who sees God in a sunset, on the other hand, is not suggesting the sunset looks like God. So pareidolia can’t explain what’s going on here.

So what else might be going on?

The philosopher Karl Popper is best known for falsificationism – a theory about how science progresses, In a nutshell: Popper says science progresses, not through theories being confirmed, but through them being falsified: shown to be false. I don’t sign up to falsificationism, but Popper does provide the following valuable insight,

When people have committed to a belief system, they tend to find ways to defend it come-what-may. Some theories are so vague that, no matter what’s observed, followers can always find a way to make it ‘fit’ – that’s to say, to make it consistent with – the evidence.

For example, suppose I claim all dogs are heavy. You point out that I’m mistaken: chihuahuas are light. However, because ‘heavy’ is vague, I can wriggle out of this apparent falsification: ‘Oh, by ‘heavy’ I meant weigh more than an ounce.’ Theories stated with mathematical precision on the other hand (‘All dogs weight more than 150 grammes’) are much more easily refuted.

Other times we defend our theories by cooking up explanations: I claim dogs are spies from Venus. You point out dogs cannot even speak, have no method of communicating with Venus, plus Venus could never support canine life. My theory might now seem falsified. However, I can always cook up explanations: I can suggest that while dogs can speak, they’re hyper-intelligent aliens who are keeping their abilities secret. I might add that dogs communicate with Venus using transmitters located in their heads, and that they live on Venus in deep underground bunkers that protect them from the toxic Venusian atmosphere. With a little ingenuity I can similarly explain away any evidence you might throw at me.

Popper thought that theories that are either so vague they can always be shown consistent with the evidence, or else are defended by means of such endless explaining-away, are unfalsifiable pseudoscience. Popper claimed Freud’s and Adler’s theories of the unconscious were so vague as to be unfalsifiable. And he insisted that Marx’s theory of history, which predicted revolution in technologically advanced England, not comparatively backwards Russia, was thereby falsified, but was then endlessly defended by its proponents by them adopting the strategy of endless explaining-way. Consequently, defenders of all these theories found that, no matter what was observed, they could always make their theory ‘fit.’

The more habitual becomes the strategy of forcing the evidence to fit your theory, the more the world may seem endlessly to confirm that theory. You may start to think: ‘Everything seems to fit! Everything now makes sense!’ In fact, the truth of your theory may even begin to seem blindingly obvious. So obvious that you may start to wonder why others can’t see it too. ‘Surely, they must be deluded, deceived, or even wilfully blind?’ Popper writes:

I found that those of my friends who were admirers of Marx, Freud, and Adler, were impressed by a number of points common to these theories, and especially by their apparent explanatory power. These theories appear to be able to explain practically everything that happened within the fields to which they referred. The study of any of them seemed to have the effect of an intellectual conversion or revelation, open your eyes to a new truth hidden from those not yet initiated. Once your eyes were thus opened you saw confirmed instances everywhere: the world was full of verifications of the theory.

Once your eyes were thus opened you saw confirmed instances everywhere: the world was full of verifications of the theory.

Whatever happened always confirmed it. Thus its truth appeared manifest; and unbelievers were clearly people who did not want to see the manifest truth; who refuse to see it, either because it was against their class interest, or because of their repressions which were still ‘un-analyzed’ and crying aloud for treatment. Source.

So here is another possible diagnosis of the experience of seeing meaning, significance, and even divinity the world. Those who adopt a religious or spiritual perspective – and who defend it come-what-may by means of some combination of explaining away and appeals to vagueness, mystery, and so on – may find it ‘fits’ the world so perfectly and obviously that, for them, the real mystery is why others can’t see it too.

So, can some people really detect meaning, significance, and even divinity in the natural world, or are they projecting? On the one hand, it’s certainly possible that at least some of these experiences are genuinely revelatory. On the other hand, we know that we humans are peculiarly prone to seeing what’s not really there, and, in particular, to thinking we’re detecting agency where in truth there is none.

Stephen Law is a philosopher and author based at the University of Oxford. He researches primarily in the fields of philosophy of religion, philosophy of mind, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and essentialism. He is author of numerous popular books, including The War for Children’s Minds. Read more of his essays here.