A team of researchers works to develop an understanding of the global religious population — and predict how that population will change in the next thirty years.

In 2017’s polarized political climate, common ground is hard to come by. One exception? The Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project.

In “Hawaii v Trump,” a court fight over President Trump’s Muslim travel ban in March, both the State of Hawaii and the Trump administration cited the work, which is based on a six-year analysis of the evolution of religious traditions around the world, to back their arguments. In particular, both sides referenced the project’s statistics on the world’s Muslim population.

Such inclusion speaks to both the rigorous nature of the research methods and the lack of previous research on the topic. “When we began this not very many years ago, there was no broadly accepted number for how many Muslims there were in the world — estimates were really all over the map,” says Alan Cooperman, author of the project study and director of religion research at the Pew Research Center.

Cooperman’s work is part of a series of Pew Research Center projects funded by the John Templeton Foundation. The Foundation donated a total of $6.9 million over first three phases, allocating $2.6 million to this third phase, as well as an additional $2.4 million to the current, fourth, phase. The Pew Charitable Trusts has also provided generous support to the project. Cooperman worked with a team of demographers and researchers to not only accurately place the worldwide Muslim population, but also to offer an estimate of how all world religions will change by 2050. More broadly, the project examined religious freedom around the world and public attitudes toward religion.

Gathering the Data

The first challenge — and a significant one, it turned out — was collecting accurate religious population data. Conrad Hackett, Pew’s associate director of research and senior demographer, points out that most census bureaus don’t ask about religion — including the U.S. Census Bureau.

“There are surveys that ask about religion [in the U.S.], so those are pretty good for getting a sense for how many are Catholic or Protestant, but getting a good measure of the American Muslim population, which includes a large number of immigrants who may not speak English well for a phone survey, is something that’s tricky to do,” Hackett says. Compiling accurate figures for religious affiliation among various populations was no small task. The team’s goal in doing this research was to dispel lingering misconceptions about global religions.

“A lot of people have perceptions about the world that don’t match up with the data,” Hackett says. “A lot of people think most Muslims are in [only in] the Middle East but they’re not.” In addition, the largest non-affiliated populations aren’t in the U.S. or Europe, but in Asia. “Having this global perspective helps us see how our experience in the United States doesn’t reflect the global experience.”

Findings Show Growth of Islam, Relative Decline of ‘Nones’

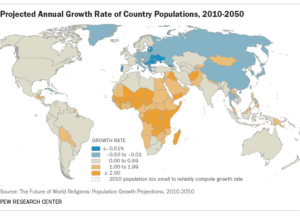

In addition to demographic information, the study also sought to project how such religions will grow during the next few decades. The team looked at fertility rates, the average ages of citizens with various religious affiliations, mortality rates, immigration, and migration to extrapolate a vision for how the world’s religions will look in 2050.

One of the major findings of the study — which was covered in some 500 news stories in 2015 — was that Islam is growing faster than the other major world religions. By 2050, Christianity will still be the world’s predominant religion, but it won’t be as dominant in some parts of the world. For instance, in the U.S., the Christian population is expected to shrink from three-quarters to two-thirds, and Islam will supplant Judaism as the country’s second-largest religion, according to the organization’s projections. India will also become the world’s largest Muslim nation, and Muslims will make up 10 percent of the European population.

One of the major findings of the study — which was covered in some 500 news stories in 2015 — was that Islam is growing faster than the other major world religions. By 2050, Christianity will still be the world’s predominant religion, but it won’t be as dominant in some parts of the world. For instance, in the U.S., the Christian population is expected to shrink from three-quarters to two-thirds, and Islam will supplant Judaism as the country’s second-largest religion, according to the organization’s projections. India will also become the world’s largest Muslim nation, and Muslims will make up 10 percent of the European population.

Another key finding was that the global percentage of the population that is unaffiliated with any religion, the so-called “nones,” will also decline. Why? The religiously unaffiliated tend to reproduce less frequently, and many of the world’s “nones” in China are moving towards some kind of religious affiliation, such as Confucian, Christian, or Buddhist.

Publishing Demographic Projections

In addition to the broader demographic reports and projections, the third phase of the Pew Research project included a more in-depth survey of religion across 18 countries in Latin America. The organization also began a similar survey across Central and Eastern Europe, including many formerly Communist nations where religion was banned or discouraged in the past, the results of which Cooperman’s team published in May.

The Global Religious Futures Project Phase Three is one of four phases. In the first two phases, which ran from 2010 to 2013, the researchers looked the current size and geographic distribution of the world’s major religious groups. Those phases also included major international surveys, first across 19 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and then across 26 additional countries in the Middle East, North Africa and parts of Asia with large Muslim populations.

The third phase’s work carries over into the current, fourth phase, which also looks at religion and gender and educational attainment levels of the world’s major religious group. The researchers are also preparing to field a major survey of religion in Western Europe. The fourth phase, which began in 2016, will be completed this year.